content body

A seasoned researcher and administrator in the Auburn University College of Agriculture and one of the top 2% of entomologists in the world got her start in the field because of the kindness of a neighbor.

Nannan Liu grew up in Beijing in a community full of scientists.

“My parents are biologists,” she explained. “There, you live with the institute. Like our campus here, but we all lived in the institute. Which meant that when I was younger, I was exposed to all these scientists like my parents. And my neighbor was a well-known professor of entomology.”

Liu recalled how her neighbor would show newly acquired specimens to the children in their community. It captured her attention, and entomology has held it ever since.

Today Liu is an endowed professor in the Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology at Auburn. She is also currently interim head of the Department of Poultry Science.

Despite an early interest in the field, Liu did not necessarily set her sights on a career in agriculture. In China, application to college worked differently than it does in the U.S. Students would take an entrance exam not unlike the ACT or SAT, and universities could select students based on their scores. China Agricultural University visited Liu’s province and set its sights on her.

“I really did not have any idea about China Agricultural University, as it is known today,” said the alumna of the school. “At the time, I selected some others I wanted to go to.”

Fortunately, that seed planted early by her neighbor blossomed into a passion. After graduation, Liu worked a short time for the Ministry of Agriculture — “kind of like the Environmental Protection Agency here,” she explained — before she was sent to Queensland Department of Agriculture and Primary Industries in Queensland, Australia.

“I thought maybe I was done with studies,” she reflected. “But I realized, I needed more knowledge. I just thought, ‘I need to study.’”

So, she came to the U.S. for a Ph.D. program at Cornell University. And she never left.

At Cornell, Liu began the research that would carry her through her career. Her specialty is in insect molecular toxicology, or the study of insect resistance to insecticides and poisons at a molecular level.

It is a crucial field of study for our world: How do we treat disease carrying insects or pests that affect our food supply? Why do they resist treatments?

Her work at Cornell began this research with house flies, looking at the mechanism of gene function. She then went to Rochester Medical School for a postdoc, learning new-to-her research techniques before returning to Cornell for further study of gene regulation.

She came to Auburn as an assistant professor in 1997 with a 75% research and 25% teaching appointment. Her research with the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station has flourished in her more than 25 years at Auburn, something she credits to her department.

“I like research here,” she said simply. “We are provided what we need to be successful in our research. But it is also very collaborative, and the administration is very supportive of faculty.”

Liu joined the administration for the first time in 2014, serving her first three years as chair of the Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology. The position has a limit of two three-year terms and she was elected chair again for another three years from 2017-2020.

“By that time, I looked at my development, my achievements, my research parts, my group, my student and postdoc, all that,” she said. “Everyone was very independent. I saw the opportunity to develop myself and to bring our two disciplines of entomology and plant pathology together.

“When you are the professor or just a researcher, you may be more focused on your own research, right? However, when you are the chair, you communicate with everybody. And you have the opportunity for learning, for new things.”

In her time as chair, the department’s faculty size doubled.

“Dr. Liu was a kind and considerate department chair who led by example,” said Arthur Appel, current associate dean for research and Liu’s predecessor as chair of the department. “While chair, she had a full and active lab group, wrote numerous research publications, applied for grants and taught her courses.”

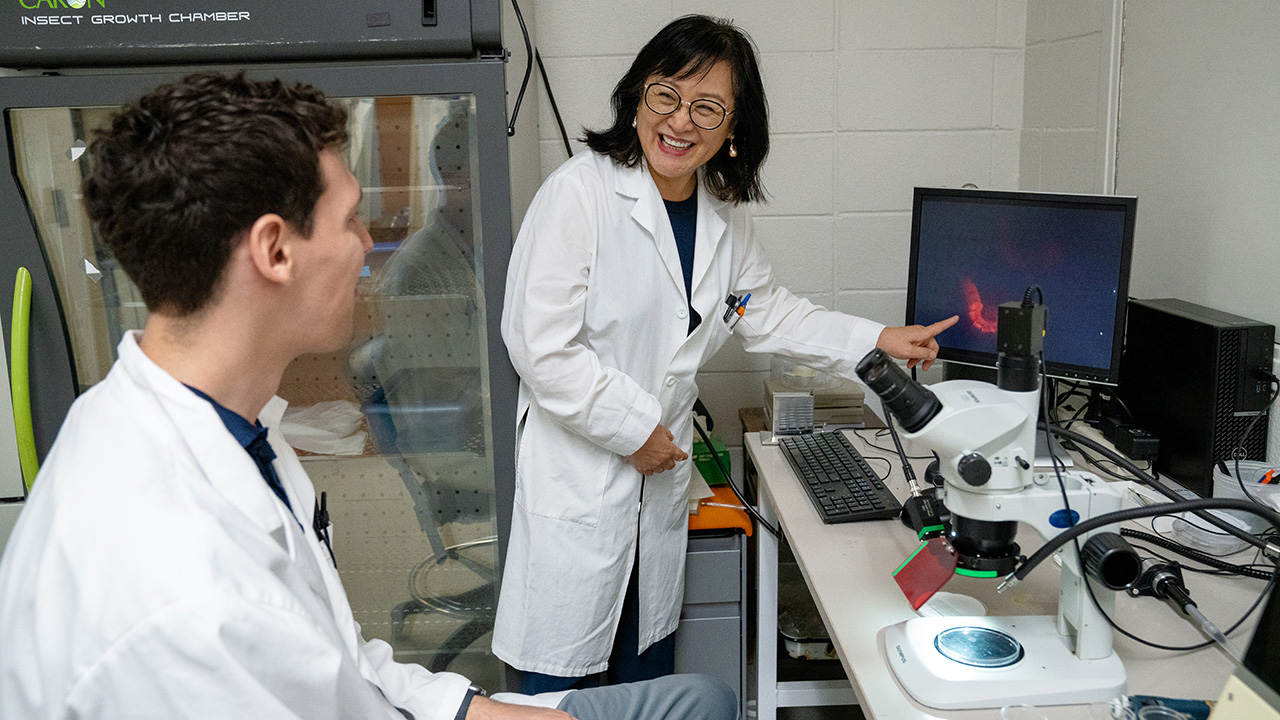

Liu’s lab remains a stronghold of research in the college. Their study of the mechanisms of gene function has looked at flies, bed bugs and now mosquitos, asking how genes are regulated in an organism in response to chemicals, and what happens if the organism loses those genes.

She is uncommonly proud of the graduate students she has advised over the years, and the respect and admiration they have for her is clear. All her past Ph.D. students have given her their tassels upon graduation, which she proudly displays on a bulletin board in her office.

Her newest project, funded by the National Institute of Health, is looking at the olfactory system of mosquitos, asking how scent plays a part in what draws mosquitos to people, and what happens if you knock out the mosquito’s olfactory response.

Mosquito-borne diseases, in particular malaria, are among the leading causes of human deaths worldwide. In past decades, massive spraying of insecticides greatly limited these diseases and even eradicated them in a few countries. However, a wide-spread increase in mosquitoes’ resistance to insecticides is now resulting in outbreaks of mosquito-related diseases, including malaria, around the world.

The long-term goals of this research are to better understand the molecular mechanisms and regulatory pathways that control the mosquito’s response to insecticides and to use these findings to inform the development of insecticides that not only control mosquito proliferation but also thwart insecticide resistance, ultimately reducing the incidence of mosquito-borne diseases in humans.

“That is mainly what we still work on,” she said. “We try to thoroughly understand the regulation pathways involved in resistance, yet this pathway has not been reported before. Therefore, we want to pinpoint and eventually offer a comprehensive picture about resistance, how it is regulated at the molecular level. With this comprehension, we envision developing a novel method to block this pathway, preventing insects from developing resistance.

“The ultimate goal, of course, is to prevent mosquito bites. But we’re approaching this with the broader perspective — resistance studies. That’s really what I’ve been doing since the ‘80s.”

The work didn’t stop as Liu stepped in to serve as interim head of the Department of Poultry Science, a move she considered a perfect segue for her, as the house flies she started her studies in are commonly found in poultry farms.

“Dr. Liu is one of the top 2% of entomology researchers worldwide, has been named a Fellow of the Entomological Society of America, and is an internationally recognized insect toxicologist,” Appel said. “Her research is both basic and applied and uses the latest cutting-edge methods in molecular biology and neurophysiology. She is an excellent colleague and outstanding scientist.”

For Liu, it’s just all in a day’s work.

“I don’t want to just be comfortable,” she said. “And there are so many questions still to answer.”