content body

A collaborative study between Auburn University’s College of Sciences and Mathematics (COSAM), the Department of Biological Sciences, George Mason University and the Smithsonian Institution has shed light on the fascinating interplay of genetics, sexual selection and natural selection in shaping bird coloration.

Researchers, including Auburn’s Geoffrey Hill and postdoctoral fellow Matt Powers, contributed to this project, which reveals how genetic and structural traits influence plumage color and its evolutionary implications.

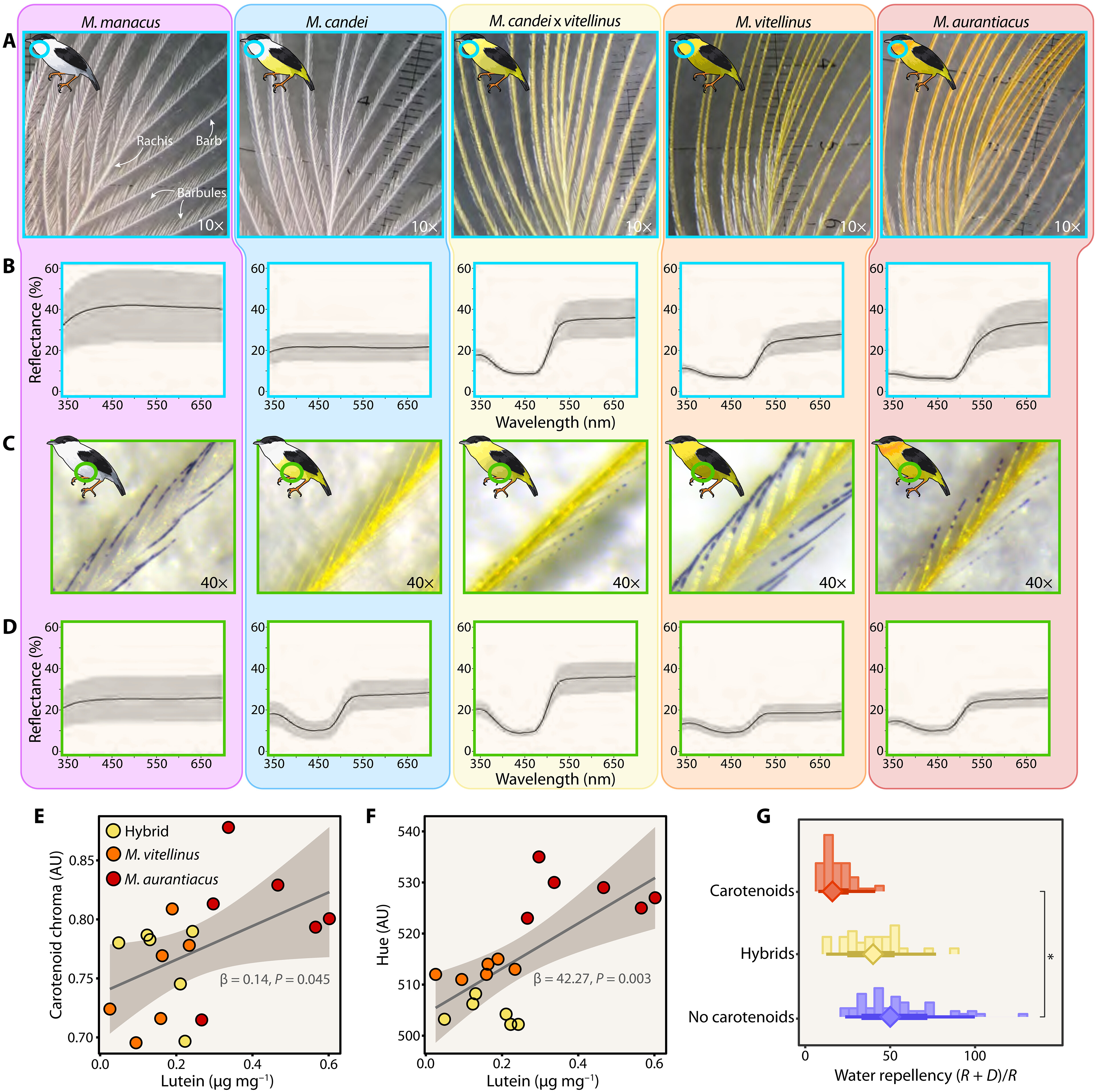

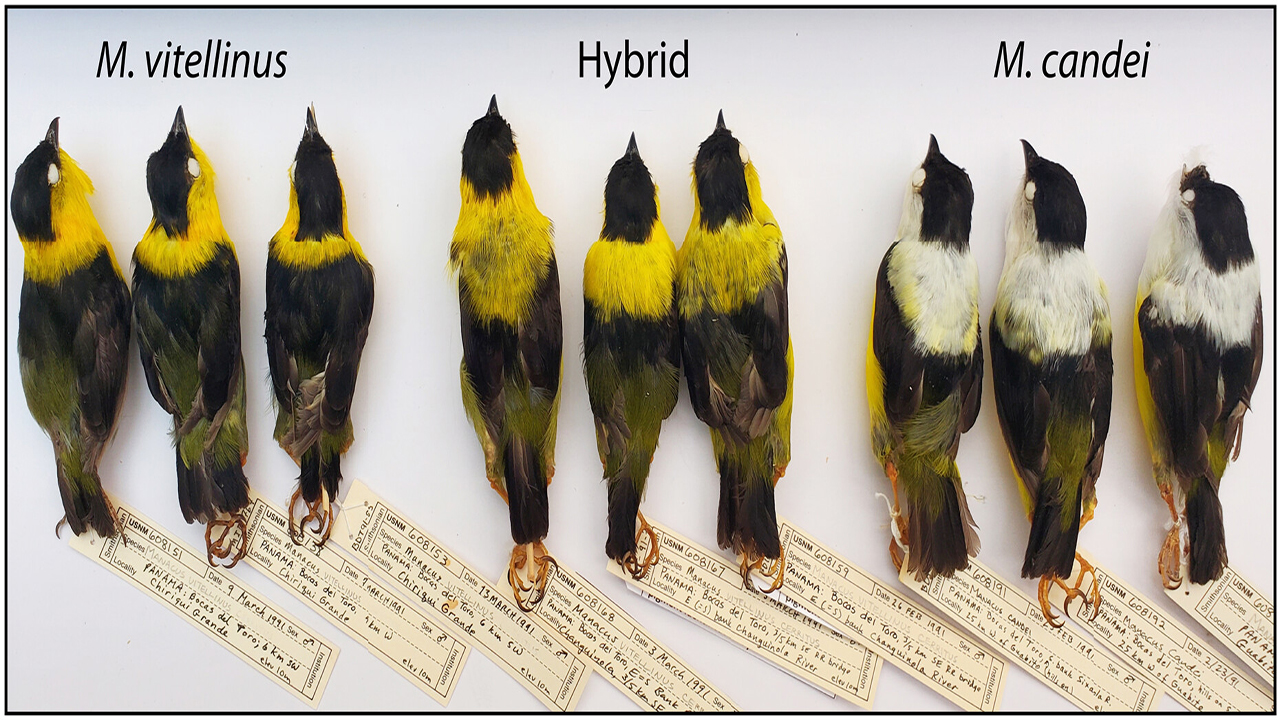

The research focuses on a hybrid zone in Central America where two closely related bird species meet and mate. Over time, the yellow plumage of one species has replaced the white plumage of the other in this area — a process driven by female preference for brightly colored males. This shift, however, comes with trade-offs, as the vibrant feathers are less water-resistant, potentially affecting survival in the birds' tropical environment.

Hill emphasized the evolutionary dynamics at play.

“This project showcases the tug-of-war between natural and sexual selection,” Hill said. “Sexual selection favors bright yellow plumage for mating success, but natural selection resists due to the reduced waterproofness of yellow feathers. It’s a fascinating example of how opposing forces shape species.”

Auburn’s team analyzed carotenoid pigments in the birds' feathers. These pigments, specifically lutein, are responsible for the yellow coloration. Hill’s lab also examined how the structure of yellow feathers enhances their brightness but compromises their waterproofing — a significant adaptation challenge for tropical birds.

Powers, who conducted the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis and statistical modeling, reflected on the significance of the research.

“What’s remarkable is the simplicity of the genetic mechanism behind this color variation,” he said. “A single gene, BCO2, determines whether a bird is yellow or white by controlling carotenoid breakdown. It’s rare to see such a straightforward one-to-one relationship in biology.”

The research highlights the evolutionary journey of plumage traits. Genetic analysis revealed that the yellow pigment likely originated in a third bird species and spread into the hybrid zone through historical gene flow. This underscores the complexity of hybridization and its role in shaping species.

Powers also noted the importance of collaboration in bringing the project to life.

“The integration of genomic data with feather pigment analysis was a monumental effort, spanning years and multiple institutions,” he said. “It’s a testament to what’s possible when diverse expertise comes together.”

Hill hinted at a secondary discovery by the Smithsonian team that remains unpublished, suggesting there is more to learn from this collaborative work. Both Hill and Powers expressed excitement about the ongoing potential of their research, which began with a study led by a prominent ornithologist in the 1990s and has since evolved into a multi-disciplinary investigation.

By combining advanced genetic tools and pigment analysis, this study not only advances the understanding of bird evolution but also offers new insights into genetics with potential applications in human biology. Auburn's role in this collaboration underscores its commitment to impactful research and interdisciplinary innovation.