content body

Auburn physics graduate student Shawn Oset was “in the right place at the right time” to help capture data on interstellar object 3I/ATLAS.

When a rare object from another star system barreled through our solar system this summer, two physicists in the College of Sciences and Mathematics didn’t just watch from afar. They grabbed their telescopes, rallied their team and helped make history.

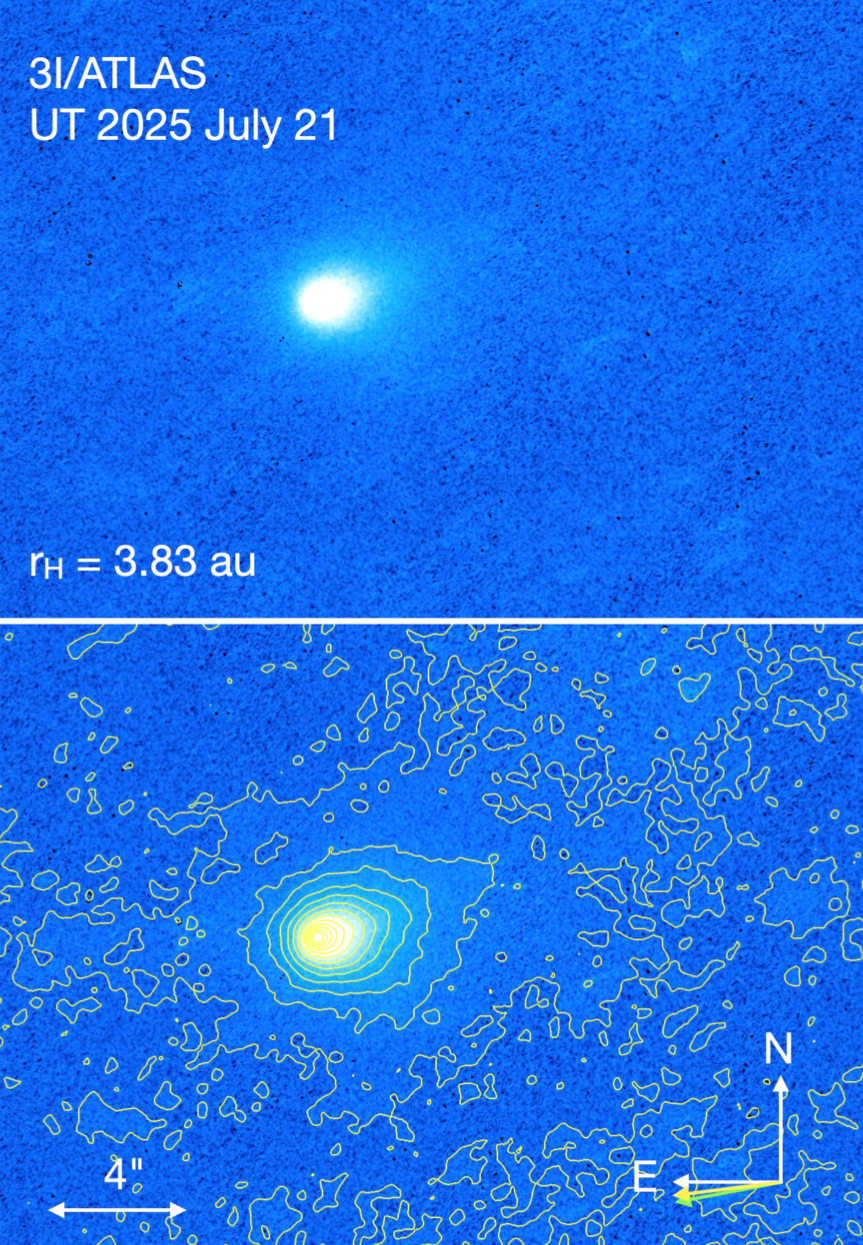

Shawn Oset, a graduate student in Auburn’s Department of Physics, was “in the right place at the right time” to add an interstellar object to the data set he studies — modeling cometary comae, the clouds of gas and dust that surround a comet’s nucleus, using ultraviolet observations from NASA’s Swift satellite. Swift, launched in 2004 to study distant gamma-ray bursts, can also detect ultraviolet light invisible from the ground, making it a powerful tool for studying comets and other small bodies in the solar system.

Zexi Xing, a postdoctoral researcher working with Professor Dennis Bodewits, first got into this field in 2019 studying the second known interstellar object, a project that led to her postdoc. “Now,” she said, “I’m lucky enough to catch another one.”

Both are part of Auburn’s Laboratory for Astronomical and Space Observations (Lab Astro) group. When 3I/ATLAS appeared, Oset and Xing helped lead an international effort that moved from first observation to a finished scientific paper in just days.

The object’s speed and fleeting visibility made every observation count, and what the team found could reshape how scientists view interstellar visitors.

Q: What did you observe and why does it matter?

Oset: We were the first to detect traces of water from 3I/ATLAS, which gives us valuable information about material conditions far away and possibly very far back in time. Among many other things, this informs models of planetary formation, dynamics and disk chemistry, and because water is foundational to life, the more we know, the better.

Xing: 3I/ATLAS is only the third interstellar object humans have ever discovered. We had this tiny window to observe it as it zipped through the solar system, and we likely detected OH. Since OH is a proxy of water, this gives us precious clues about the history and origin of this cosmic wanderer.

Auburn postdoctoral researcher Zexi Xing co-led the international effort to observe and publish findings on interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS.

Q: You went from discovery to paper in days. How?

Oset: Hard work! It’s the culmination of years of team experience analyzing Swift data. We’ve built in-house data reduction pipelines that let us move quickly and confidently, so once we get results, we can collaborate on what they mean and how to communicate them.

Xing: We observed on Friday, spent the weekend analyzing the data and started writing on Monday. We pulled everything together and wrote the whole paper in a single day. Everyone knew what to do and we helped each other out. That’s crazy!

Q: What role did Swift play?

Oset: The Ultraviolet and Optical Telescope (UVOT) on board the Swift satellite took the images we used for our analysis. Swift was launched to study gamma-ray bursts, so we are grateful for the flexibility the Swift team continues to show by pointing their instrument at something it was not intended for. As of this discovery, Dr. Bodewits and Zexi have now used Swift to find water in two interstellar comets, 3I/ATLAS and 2I/Borisov.

Xing: UVOT can see things that telescopes on the ground miss, like OH signals from comets. Swift is also super quick and flexible to respond, so we started observing 3I just two weeks after its discovery. However, 3I was really fast, faint and far away, so we needed some special tricks for it. The Swift team helped us figure everything out and made it all work. Dr. Bodewits joked that we were doing ‘acrobatics’ with Swift!

NASA’s Swift satellite provided ultraviolet images of 3I/ATLAS, enabling Auburn researchers to detect traces of water from this rare interstellar visitor.

Q: What makes 3I/ATLAS stand out?

Oset: It’s only the third detected interstellar object to enter the solar system. The first had no water, the second had detectable amounts, so we’re still trying to understand the composition of a typical interstellar visitor. What really sets 3I/Atlas apart is its high speed and the possibility that it is extremely old, which would make it a time capsule from billions of years in the past.

Xing: 3I/ATLAS is like a messenger telling us about stellar systems we'll never be able to reach. Many human questions — what distant worlds are like, how they compare to our own — might find clues from this visitor. It’s a piece from another planetary system, flying through our own! We think that ‘our’ comets delivered water and organics to Earth, so we really want to know what these interstellar comets are made of.

Q: How did you contribute to the project?

Oset: Both Zexi and I did an analysis in parallel as soon as the data arrived. Once our team confirmed the results, everyone immediately started writing. The depth of knowledge of Dr. Noonan and Dr. Bodewits on the subject meant that we could contextualize our findings quickly. I felt confident taking this project on, knowing that I could rely on their guidance and rely on Zexi to tell me when my numbers are wrong!

Xing: Dr. Bodewits immediately submitted the Swift observation request after 3I's discovery, and I planned the specific observation modes and timing. We all participated in paper writing. It's so exciting to see the whole comet community discussing the same object at the same time!

Q: Advice for others who want to do this kind of work?

Oset: To the students, take all the physics and astronomy classes you can and get comfortable coding in Python. There is no escaping it in astrophysics. To the early-career researchers, get in touch with someone in the field. They’re incredibly nice people.

Xing: Don't fear confusion or doubt. They’re signs you're thinking and being curious!