content body

You are Mahatma Ghandhi. What decisions should you make as you seek to unite your people in seeking independence from the British Empire? One of your classmates is inspired by a philosopher. What arguments will they launch as they try to persuade you to adopt an entirely new form of government in eighteenth-century France?

For several years Kate Craig, associate professor of History with the College of Liberal Arts and recipient of the Honors College’s Outstanding Faculty Award in 2018, has taught History 1017 and 1027, Honors versions of World History I and II, through a model she calls “Reacting to the Past.” These courses have merited rave reviews from students.

Andrew Hough, an Honors junior majoring in accounting who is currently taking World History II, spoke for many when he commented, “This is the most engaging and active learning experience I’ve had in my academic career.”

Not reenactment but reacting

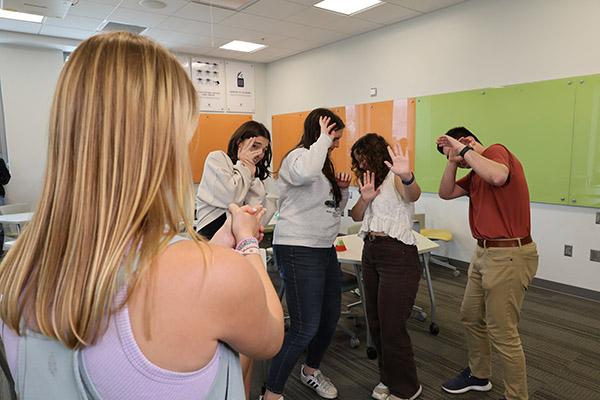

Craig teaches both courses through a series of role-playing games that are bracketed by more traditional forms of classroom interaction.

Roles are assigned at the beginning of each of the three games that are played over the semester. Their task is not simply to re-enact past events, but to approach a game structured around an event like the French Revolution as though it were unfolding in that moment, with outcomes determined by the actions that the characters take during the game.

Students defend the perspectives and decisions of their assigned characters in accompanying debates. Finally, students step out of their roles to engage in detached “post-mortems” as they compare the game’s outcomes with the historical record.

“History has many lessons for our global present and future, but it can be hard to see that when you are just reading names and dates off a page,” Craig explained. “A reacting game places you into the historical moment and makes you an active participant, so you can see for yourself how complicated the issues were.”

Part of the payoff of this approach is that students realize that the past was not predetermined: History could have turned out many ways. Students also develop a new appreciation of the roles they play in the present day.

“They appreciate that the future is not yet written; what we choose to do now matters,” Craig said.

Craig cited a former colleague, Sarah Hamilton, as an inspiration for this teaching approach. Hamilton, who now teaches in Norway, first taught the World History II “Reacting to the Past” course. After observing Hamilton’s class, Craig was deeply impressed by how engaged the students were, and she designed World History I on the same pedagogical model.

The response is enthusiastic

The Reacting to the Past courses have acquired an enthusiastic following among Honors students.

“I have never been so engaged in a class,” responded Cate Wilber, an Honors sophomore majoring in law and justice. “I’ve not only learned more than I’ve ever known about political history, but I find myself wanting to step outside my comfort zone.”

Carlin Bates, an Honors sophomore majoring in biomedical sciences, took World History I in her first semester, and praised how the course had built a sense of community for her in the Honors College.

“I met so many amazing people where we bonded over the unique class style,” Bates said.

Most of all, students described how the course had changed them, prompting them to see the world differently.

“I love to debate from a point of view of which I would not usually take,” Wilber noted. “I get to become a character from history that I might disagree with today. I learn from their perspective, and I find myself altering my own opinions because of what I’ve learned in class.”

This kind of response, for Craig, makes such an intensive form of teaching well worth the effort.

“Many have told me how much the class made them think about the world: what historian could wish for more than that?” she asked.

No single requirement or feature defines all Honors classes. Instead, these courses, which involve almost all fields of study, share the goal of providing intellectual enrichment for the Honors College’s students, enhancing the already rigorous offerings of an Auburn curriculum.

Taught through a variety of approaches, these courses often take advantage of smaller class sizes to utilize more active and collaborative forms of learning. Every semester the Honors newsletter will feature one or two courses that epitomize the Auburn Honors educational experience.

Story written by Laura Stevens, Honors College director.