content body

The Grand Gallery of The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University is filled with an upside-down ship-like vessel and never-before-seen oil paintings by internationally acclaimed architect and artist Walter Hood. The exhibition, “Arc of Life/Ark of Bones,” is a two-part installation that showcases the artist’s duality and latest work.

Spread across a series of 10 paintings, Hood portrays scenes from the first decade of his life in “Arc of Life,” painting figures playing, running, praying or resting. “It's pretty amazing how memory can be lucid,” Hood said. “Do I want to grab pictures of my father and paint from that? Or do I want just those figures to come out? And it's probably the latter. I'm not looking to be representational as far as through image, but it is the spaces that these paintings I'm beginning to depict."

Born into a military family in North Carolina, Hood spent his early years in the 1960s abroad, steeped in other cultures—an experience that shaped his perception of society and his place in it. “I didn’t have an understanding that we lived in a segregated world,” said the artist. As the Civil Rights Movement unfolded across Hood’s primary and secondary schooling, his awareness of societal inequities began to grow, before he eventually opted to pursue college at North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black university.

“It gave me a clearer contextual environment to navigate and figure all this stuff out— because the world, I mean, was still black and white in North Carolina,” Hood said. “But it was a time when I was nurtured enough so that when I did finally go out into the world, I had a sense of who I was, where I came from and what I could do.”

Despite his childhood interest in drawing, Hood’s position as a first-generation college student compelled him to study landscape architecture, only shifting to painting after years of practice and teaching. He was awarded the Rome Prize in the late 1990s to work in Italy before later continuing his artistic studies at the Art Institute of Chicago. “Arc of Life” marks his first solo museum exhibition for painting.

The painted works reflect Hood’s experiences growing up with segregation and integration through the 1970s. “I wanted to talk about this notion of the kind of pain, the kind of joy that exists in Black life that I can remember,” he said. “My parents probably shielded certain things away from me to allow normality to happen until I got to the point where I could actually see it or that it somehow seeped in. And then there were these moments of sadness like Lorraine [Motel]—when King died. Lorraine has stayed with me more than anything. Just that name.”

A MacArthur Fellow, Hood is the creative director and founder of Hood Design Studio in Oakland, California, a cultural practice, working across art, fabrication, design, landscape, research and urbanism. He is also the chair and professor of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planning and Urban Design at the University of California, Berkeley.

"House of Generations"

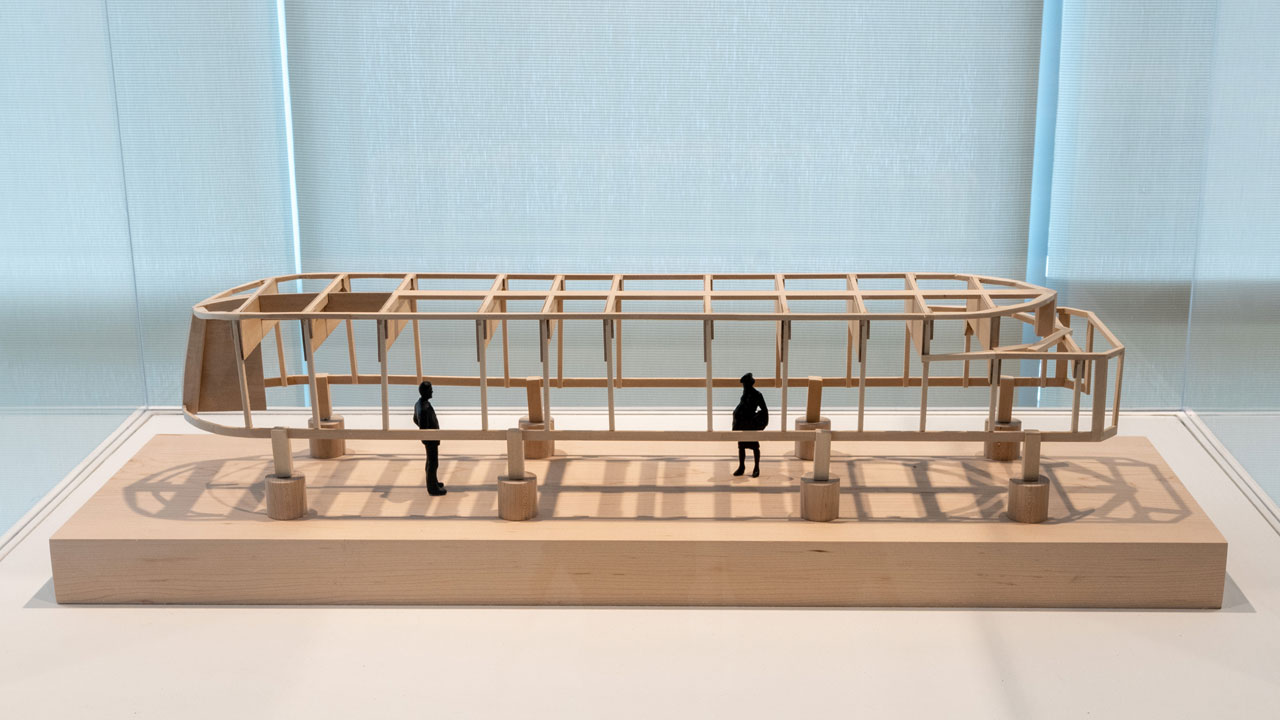

The installation’s second half, “Ark of Bones,” speaks to Hood’s more traditional background as an architect. “The idea comes from coming to Alabama and being blown away by the experiences, the people and the landscapes themselves,” Hood said, revealing he was also inspired by the Alabama River and the complex symbolism behind water. “Early as a landscape architect, hydrology is central to what you think about — moving water off of surfaces,” said Hood. “Being from the South, North Carolina, my mother was baptized in the river.”

The installation’s name, “Ark of Bones,” hails from the eponymous Henry Dumas short story, in which two young boys meet an otherworldly man leading an ark down the river. The elder describes the boat as the “house of generations,” saying “every African who lives in America has a part of his soul in this ark.” As the story conveys, the ark is filled with the past—a place where the entire history of a people is kept, harkening back to Hood’s paintings showing his upbringing through the 1970s.

A forum for Southern art and culture

To develop his proposal, he also focused on Auburn’s geographical location relative to key sites in American history, both those in the past and ones unfolding. “I felt that I could have a conversation with the types of exhibitions and conversations happening in Montgomery and Mobile,” Hood added, referring to the work of The Legacy Museum and the historical significance of The Clotilda discovery.

The museum’s executive director, Cindi Malinick, praised Hood’s piece for its relevance to multiple academic fields across campus and how it feeds into the museum’s work of navigating conversations and histories as part of an elevated student education. “This project naturally connects to Auburn’s top-ranking College of Architecture, Design and Construction,” she said, “but there are multiple applications for students pursuing a variety of interests from studio art to interior design to history. The Jule prides itself in the work it does as a museum to nurture the natural curiosity of all students.”

Marketing major and the museum’s student advisory board president, Kezia Akwensi, connected with Hood’s work herself. “In one of his paintings, a person is lying on a bed with a Jackson Five poster hanging on the wall,” she said. “It reminded me of when I was younger and living at home with my mom, laying down on a sunny day and listening to music.” She also noted how important the museum is to her college education and overall student experiences. “It broadens their view of life,” she said. “The museum gives them a new perspective that they may not have thought about before.”

Hood’s most recent campus visit was for the inaugural “Auburn Forum on Southern Art and Culture,” held on Saturday, February 3, where he joined exhibiting artists Bethany Collins, Lonnie Holley and Elizabeth M. Webb in a series of conversations before a student, faculty and community audience. The museum aims for the Auburn Forum to become an annual tradition, attracting leading scholars, artists and the public, encouraging engagement in critical dialogues about the South’s rich and multifaceted artistic landscape.

Speaking at the Auburn Forum with Taneshia West Albert, assistant professor of interior design in Auburn’s College of Human Sciences, Hood spoke about the influence of community and needs of people on his approach to designs with his studio. “We try to use art to illuminate where people are,” he said. “Sometimes, it gets them to do something.”

The Auburn Forum On Demand

Walter Hood joins exhibiting artists and scholars from Auburn, Northwestern and Stanford Universities in a series of one-on-one conversations.

Watch