content body

Artist Lonnie Holley speaks with Stanford's Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander at Auburn's art museum. Photo by Stew Milne.

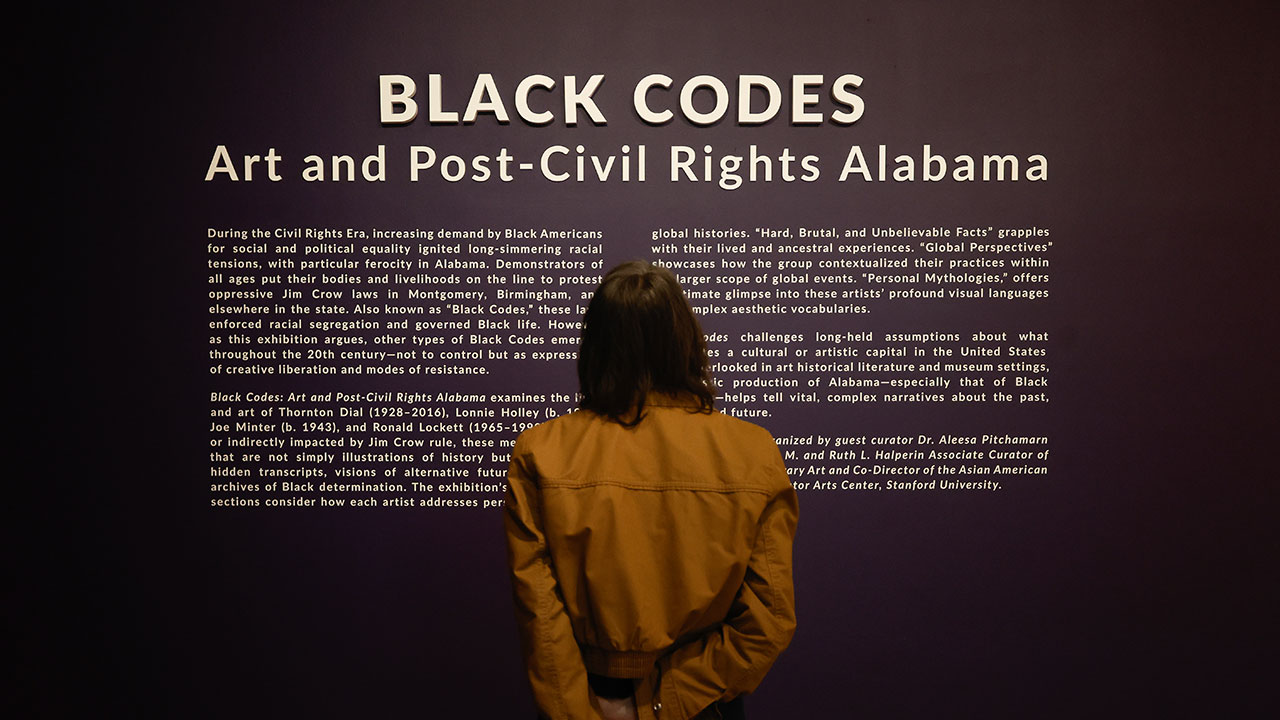

“Black Codes: Art and Post-Civil Rights Alabama,” a guest-curated exhibition highlighting the lives and works of four pivotal Alabama artists, is on view at The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University. Available to the public through Sunday, July 7, “Black Codes” features works from Thornton Dial (1928 – 2016), Lonnie Holley (b. 1950), Ronald Lockett (1965 – 1998) and Joe Minter (b. 1943), artists who were directly or indirectly impacted by Jim Crow laws, also known as Black Codes.

The exhibition’s guest curator, Dr. Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, visited Auburn in the spring for the inaugural Auburn Forum for Southern Art and Culture. “I think this type of project is exactly what university art museums do best,” Alexander said. “I love university art museums because they do these types of projects that are really research-driven, embedded in history, artist-centric, asking difficult questions and examining narratives in ways that larger art museums are frankly afraid to do in significant ways.”

“We've thought a lot about what expanding research capabilities looks like for an R1 teaching museum and for Auburn more broadly,” The Jule’s executive director Cindi Malinick said. “Inviting scholars such as Dr. Alexander not only to guest curate an exhibition that features significant Southern artists, but also to join us for the Auburn Forum in conversation with Lonnie Holley, really exemplifies the serious academic work we do at The Jule and we’re always open to engaging with faculty across campus for similar endeavors."

Installation view of pieces in the "Black Codes" exhibition. Photo by Mike Cortez, The Jule Museum.

“Black Codes” stems from ideas that first germinated in Alexander’s dissertation during her time as a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Barbara. During the Civil Rights era, increasing demand by Black Americans for social and political equality ignited long-simmering racial tensions with particular ferocity in Alabama, as demonstrators put their bodies and livelihoods on the line to protest the oppressive Jim Crow rule. Alexander’s guest-curated exhibition for The Jule argues, through works from Dial, Holley, Lockett and Minter, that during the 20th century, other types of Black Codes emerged as expressions of creative liberation and means of resistance. Divided into three distinct sections, the exhibition examines how each artist addresses personal, local and global histories, compels viewers to ask who and what serves as historical record and how it’s constructed, and calls into question what constitutes a cultural and artistic capital in the U.S.

“Royal Flag,” made by Thornton Dial between 1997 and 1998, serves as an homage to Princess Diana after her death. Featuring traces of gold dust and a hand-painted rag doll among ripples of fabric stained with red, white and blue oil paints and sealing compound, Dial seems to wrestle with the ongoing legacy of the British monarchy as an institution with the woman so known for empathy and kindness, she was dubbed the “People’s Princess.”

"Ninth Ward," 2011, Thornton Dial, courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art. Photo by Mike Cortez, The Jule Museum.

Ronald Lockett, after watching a film about the Holocaust, was moved to create an eponymous work in 1988, bisected into a space of land and open air and another of walled-off darkness. Featuring metal skeletons painted stark white that appear to be falling into a pit of jet black-painted wood, the work alludes to the boxcars used by Nazis to forcibly remove and relocate Jewish Europeans into camps across Germany, Poland and other parts of Europe. Lockett’s high contrast between freedom and containment compels the audience to contemplate one of the darkest periods of modern civilization.

Joe Minter’s “Chain Gang” featuring shovels, chains and a fireplace grate, wrestles with the legacy of convict-lease labor. Thirteen shovels and two picks, crisscrossed and paired, pay homage to the Black Americans who were conscripted into a new form of slavery under Jim Crow laws, in which minor infractions transformed into serious offences, resulting in long prison sentences and the hard manual labor that supported and enriched Alabama’s iron and steel industries during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Visitors at The Jule Museum examine "Three Shovels to Bury You" by artist Lonnie Holley in The Jule Museum's "Black Codes" exhibition. Photo by Stew Milne.

Lonnie Holley’s “Three Shovels to Bury You” addresses the aftermath of the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church that catalyzed the Civil Rights Movement. Having been around the same age as the four girls who were killed changing into their choir robes, Holley constructed the sculpture from shovels, fencing, found wood and fabric so disintegrated, it begins to look like strands of hair. At the time of the bombing, Holley’s grandmother worked as a gravedigger and dug three of the four victims’ graves, according to the artist. Often thought of as frozen in time or removed from the current day, Holley’s work reminds viewers of history’s present and personal impact.

Speaking of his work and approach to artmaking with Alexander at the Auburn Forum, Holley discussed his and the other artists’ use of found materials. “I’ll go around and get material that ain’t been used by other people and put them together with a story of the people’s labor and appreciation to those people,” Holley said. “It helps you look back at your grandmama, your granddaddy, your great-grandparents, and see what they have done.”

“That’s something that I’ve always really respected about your practice – the way that you understand that materials have their own intelligences and their own histories and that part of your role as an artist is finding ways to access that,” Alexander said.

Installation view of pieces of the Personal Mythologies section from "Black Codes," on view at The Jule Museum. Photo by Mike Cortez, The Jule Museum.

One of The Jule's student guides speaks with a visitor in the "Black Codes" exhibition prior to the Auburn Forum. Photo by Stew Milne.

But the four exhibited artists did not just grapple with global and local political, cultural and historical events; Dial, Minter, Holley and Lockett were active and part of an informal artist community in the Birmingham and Bessemer areas in the 1980s and 1990s, and thus made pieces exploring themselves as individuals and their relationships with each other as artists. Many of Dial’s early pieces feature colorful tigers as stand-ins for himself and embodiments of Lockett – who was also Dial’s cousin – often portrayed as a buck. Snakes, a Biblical symbol of sin and evil, appear in pieces, as well as insects and other fauna.

Holley and Alexander talked at length during the about traditional art historical education and how Black artists, particularly the four artists exhibited in “Black Codes,” have been left out of the historical canon. “We was considered to be outsiders,” Holley said. “And we wasn’t actually being celebrated for the titles [of African American artists] that we was wearing.”

Alexander noted the divergence of academic history from the lived experiences of people as foundational to her work as a curator: “When I was in graduate school, you’re so entrenched in seminars and books, and that is where you think art history lives. But when I met you, it made me really realize that […] history lives in people, that you are the bearers of historical memory.”