content body

Brock Herron is a doctoral student in Auburn's Harbert College of Business after earning a bachelor's in animal science and a master's in food science from Auburn's College of Agriculture.

Doctoral student Brock Herron has spent the last four years studying how to safely transport food — first in Auburn University’s College of Agriculture as a master’s student in poultry science where he won the Master’s Thesis Award and currently within the Harbert College of Business’s Supply Chain Management program where he is a Presidential Scholar.

A focus on food supply chains is a fitting academic pursuit for Herron who experienced food insecurity at points in his life.

“There was a time period where I was really poor and kind of struggling to make it,” Herron said. “I really like the idea of working with humanitarian supply chains.”

Herron isn’t alone. Experts estimate that approximately one-third of college students and 34 million people across the U.S. do not have reliable access to enough food for their basic needs.

Shashank Rao, who is the Jim W. Thompson Professor in the Department of Supply Chain Management, said supply chain research, which is the study of the behind-the-scenes process for getting an item from one point to another, can provide key insights to help with this food crisis.

“There’s plenty of work out there that’ll tell you that growing enough food to support a population isn't the issue,” he said. “It’s really getting that food to where it needs to be, distribution, logistics — these are the biggest challenges.”

One example of a clog in the food supply chain process: ugly produce. These imperfectly shaped fruits and veggies — perhaps an oblong bell pepper or a curvy carrot — are perfectly tasty. But, this produce are often wasted due to its appearance, Rao said.

“Oftentimes, this produce is not picked at all. And even if it’s picked, it may be discarded right away,” Rao said. “There’s a lot of waste that happens under these kinds of inefficient channels and distribution.”

Brock Herron has been looking at how poultry, transported by truck, is often subjected to heat as the truck makes its stops. This exposure could expedite the poultry's expiration.

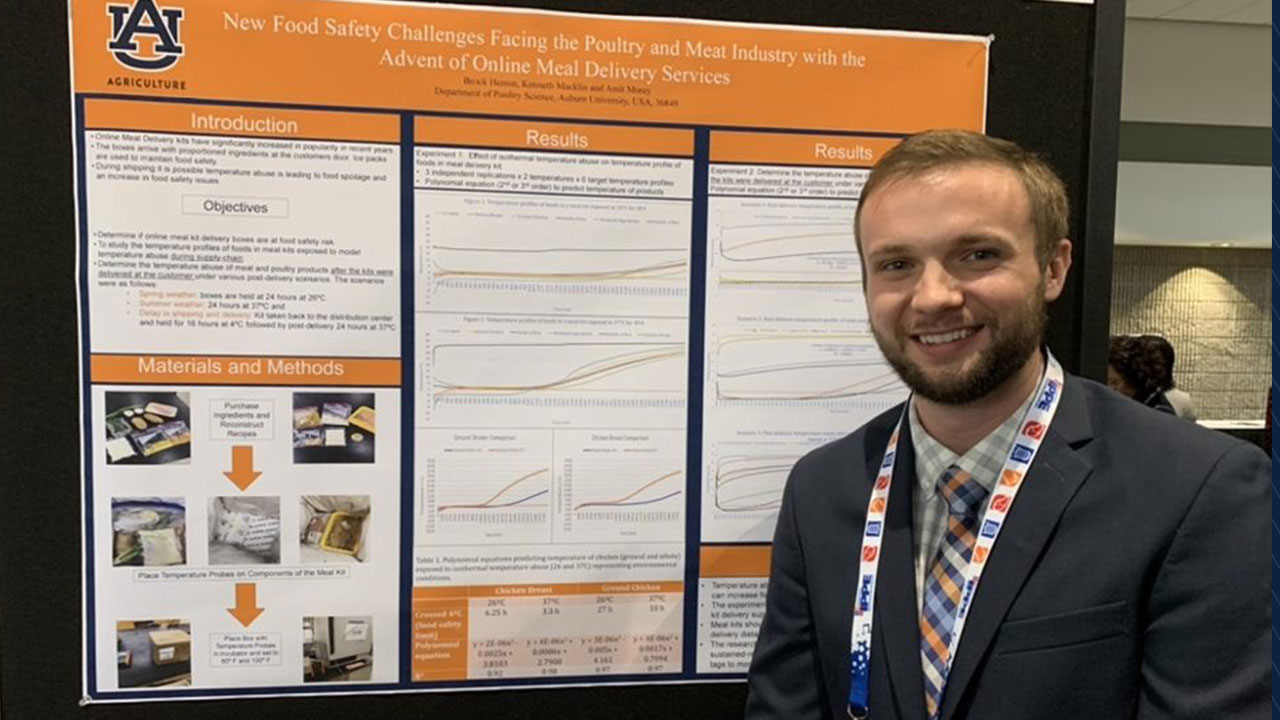

For Herron’s master’s thesis, he focused on a different aspect of the food supply chain in Amit Morey’s lab in the Department of Poultry Science: how to reduce food waste and loss, while promoting food safety.

“There’s lots of hungry people,” said Herron. “If there’s some way to minimize food waste that’s also more sustainable and better for the environment and can prevent healthy nutritious food from getting thrown away, perhaps there’s another better way of doing this.”

Herron investigated the general practice grocery stores use, known as first-in, first-out — meaning that food unloaded from trucks first should be the first to be placed on the shelves.

“This operates using the logic that product that arrives first will expire first,” Herron said. “What we were focusing on was if that logic is actually the best way of doing things.”

He specifically examined poultry that is transported on trucks that were not at full capacity, known as less-than-truckload (LTL). In these LTL scenarios, poultry is often subjected to heat as the truck makes its stops.

“Every time you open the door, the cold air comes out and the heat comes in,” he said.

Herron hypothesized that this exposure to heat could expedite poultry’s expiration, and he built models to test it.

“What we found was that product that was subjected to more temperature abuse during the delivery route before reaching the grocery store would expire before product that was not temperature abused,” he said.

This finding led Herron to propose a “first-expire, first-out” approach, in which the food that experiences the most temperature abuse would be placed on shelves first. The overarching goal: limit food waste and increase food safety.

Brock Herron has developed a fan following at conferences where people look forward to his poster to find out more about his work from year to year.

Herron went on to present his impactful research at 10 conferences, and he won the Graduate Student Award of Excellence from the International Production and Processing Expo.

“Due to his outstanding research, Brock has a fan following at conferences where people looked forward to visiting his poster to find out more about his work every year,” Morey said.

Beyond his professional success in the College of Agriculture, Herron said that he found a pivotal mentor in Morey who he describes as a father figure.

“I didn’t really have anybody else at the time to talk to if personal things happened, so I would go to him in his office,” Herron said. “He would calm me down and then help me pick up the pieces and start again.”

One day, Herron hopes he can provide the same type of empathy and listening ear for his own students. After earning his doctorate, he plans to become a professor in supply chain management.

When asked about what he would want to give to his future students, Herron said, “I would make it known that they could always talk to me about anything because that is what I needed.”

Until then, Herron is putting in the hours in the College of Business — teaching Management of Business Practices to undergraduates, enrolling in his own coursework and preparing to fine-tune his area of focus. Both Rao and Morey describe Herron as humble and a hard worker.

“Brock has been through a lot to get here, and so that really tells you that he has the kind of gumption and staying power that very few students of his age have,” Rao said. “He has the level of maturity that you typically would not expect people to have at this stage in their career.”

Herron’s life may have had as many twists and challenges as the supply chains he studies, but he said he’s glad to be in the driver’s seat now.

“I’ve always been searching for something that I could choose for myself and was not dictated based on my life’s circumstances,” Herron said. “The doctoral program was finally an opportunity where I had the freedom to choose to do something because I wanted to, not simply for survival.”