content body

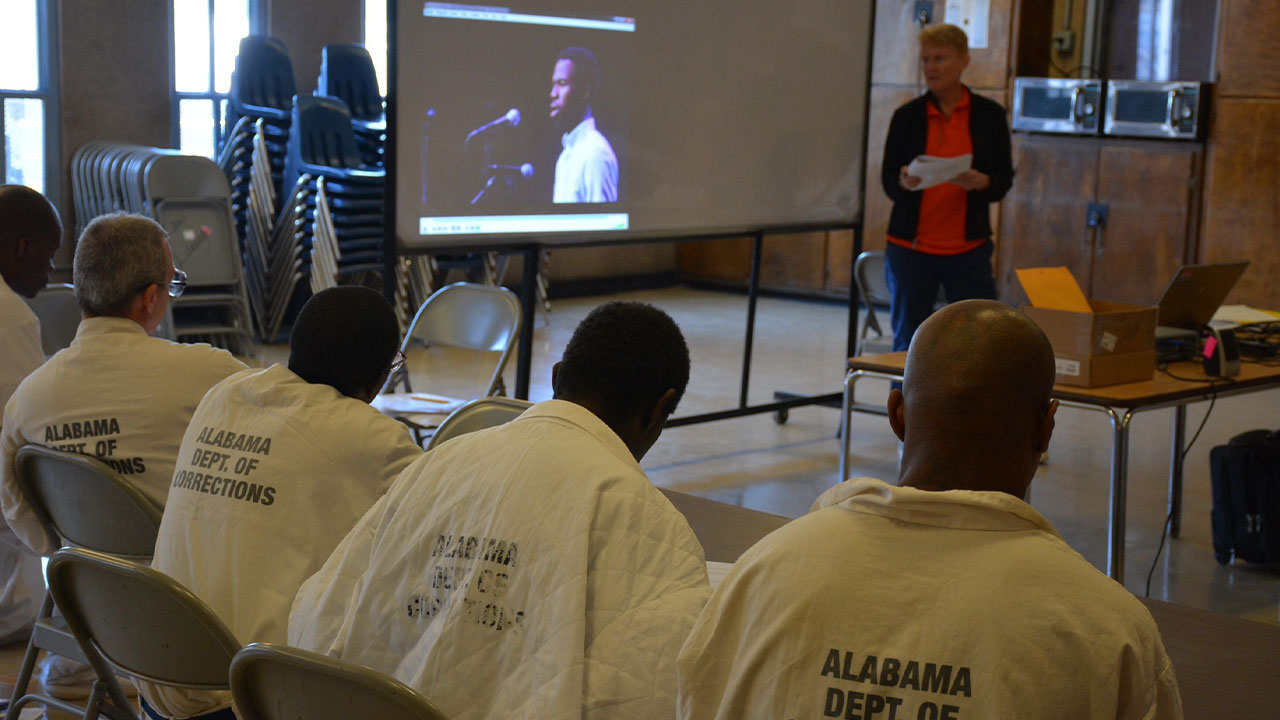

The Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project at Auburn University, in partnership with the Alabama Department of Corrections, offers not-for-credit and for-credit higher education courses in Alabama prisons, including Staton Correctional Facility in Elmore County.

Editor’s Note: The names of all the students have been changed.

A college education can mean a pathway to a brighter future, a chance for a better life. It’s that extra credential needed to land the dream job you’ve always wanted, to prepare you to improve your community.

For 11 Alabama residents, a college education means everything. They are the epitome of non-traditional students. Martin may be the only one who started down the traditional path to college as a wide-eyed 18-year-old, but circumstances changed, and he never completed his education.

Others, like Peter, admit they “squandered away” the opportunity for college while they had the chance. Kenny lived in Auburn for three years, but said he wasn’t in the right mindset back then to enroll at the university. Simply, he never imagined having a degree from Auburn University.

Since 2017, these grown men have been Auburn students. They have not only imagined earning a degree; they have worked tirelessly for it. They never entered a classroom on the Plains; their classes were held in a stark white, non-descript room at Staton Correctional Facility in Elmore County, Alabama.

These 11 students will receive their Auburn degrees on Dec. 16, one week after the university graduates nearly 2,000 students. They represent the first class of students to graduate from Auburn through the Second Chance Pell program.

“This inaugural graduation marks a huge milestone for reentry efforts in the State of Alabama,” said John Q. Hamm, commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections. “The Alabama Department of Corrections will continue its work with Auburn University and our other education partners to offer incarcerated people every opportunity for successful reentry into society.”

Bernard Lafayette Jr. is the commencement speaker for this class. He was a co-founder and leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Nashville sit-ins, a Freedom Rider, an associate of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and national coordinator of the Poor People's Campaign.

A civil rights hero and nonviolence activist, Lafayette has seen triumph and tragedy in his 83 years. He plans to share that message with the new class.

“I look forward to reflecting with the graduates on their significant accomplishment,” said Lafayette. “The fact that they were able to take classes and reach this point of graduation while incarcerated means they did not take this opportunity lightly, and now they have a chance to make a difference in the lives of others. How we respond to tragedies in life makes the difference.

“They have shown with their lives what they can do, and they are showing others in prison what is possible.”

Second Chances

The U.S. Department of Education enacted Second Chance Pell in 2016, selecting 67 colleges and universities from across the country to offer for-credit college classes to people who are incarcerated by providing them access to financial aid.

Under the new program, people who are incarcerated, who otherwise met Title IV eligibility requirements and were eligible for release, could access Pell Grants to pursue postsecondary education and training. By increasing access to high-quality educational opportunities, the goal is to help these individuals successfully transition out of prison and back into the classroom or the workforce.

“Everybody deserves some kind of chance,” said Jack, one of the 11 soon-to-be-college-graduates.

Auburn’s participation in Second Chance Pell coincides with its mission as a land-grant institution.

As a land-grant institution, Auburn University is dedicated to improving the lives of the people of Alabama, the nation and the world through forward-thinking education, life-enhancing research and scholarship and selfless service.

Most of these students could pass for a typical college student, traditional or nontraditional. Some look young, while others aged by time or the system. Their attire — prison-issued tan shirt and pants, Alabama Department of Corrections (DOC) stamped on the shirt back, black boots and a white undershirt — sets them apart though.

Before landing in Staton, Martin attended college in Birmingham for three years and was on track to complete an accounting degree.

“I’m not much different today than I was back then,” he said. “I’ve always wanted a nice job, so I could provide for my family and help my community.”

Martin said he did well in school. He took it seriously, but when he had to work two or three jobs to pay for school, his grades slipped. If he didn’t have to worry about finances, he said he could have finished.

“I didn’t ever see myself in prison,” he said. “But I lost focus.”

When Second Chance Pell became an option, Martin said he regained focus and became resolute on his goal of completing a college degree. He told Kyes Stevens he would give her his best effort.

“I made a promise to myself, to navigate beyond my past, but I will go back to the same world as before,” he said. Martin is a changed man, especially now that he has a college degree, but will the world he left behind accept him for who he is now or treat him like he is less than human?

That stigma surrounding people who are/were incarcerated is hard to overcome. It’s something Stevens has been fighting to change her entire career.

Education first

Stevens founded the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project in 2001, partnering with the DOC to offer courses on arts and humanities in Alabama prisons, and it became a program at Auburn in 2004. The project has expanded over the years to also offer not-for-credit higher education courses across many academic fields, including science, philosophy, history and engineering, in 10 of Alabama’s prisons. In 2017, Second Chance Pell allowed for-credit college courses to be taught in two Alabama prisons.

“This is about human beings who want to learn. Period,” said Stevens.

Stevens is so adamant about this belief that she has never once asked any of her students — nearly 6,000 of them — what they did to land behind bars. It has never mattered to her, and it never will.

A college education may not have been something Ted ever considered, but when he became a father, his children were his only priority. Being a college student for most of his sentence at Staton has been “one of the best things to happen to me in one of the worst environments.”

“We all know what this education means out there,” he added. “We are doubly aware of what this education means in here.”

Some would argue prison education is about rehabilitation and recidivism. A research team led by Ben Stickle at Middle Tennessee State University examined basic to college-level education in prisons, including Second Chance Pell, and found that educating people who are incarcerated reduced recidivism, improved employment prospects and increased earnings. The findings were recently published in the American Journal of Criminal Justice.

In 2016, when Second Chance Pell was announced, then-U.S. Secretary of Education John B. King Jr. said, “The evidence is clear. Promoting education and job training for incarcerated individuals makes communities safer by reducing recidivism and saves taxpayer dollars by lowering the direct and collateral costs of incarceration. … The knowledge and skills they acquire will promote successful reintegration and enable them to become active and engaged citizens.”

In Alabama, Second Chance Pell started in Staton and Tutwiler Prison for Women in Wetumpka with 25 students. Currently, there are 80 students, with 11 on track to graduate in December. Disregarding a couple of years when a global pandemic suspended classes, these 11 are graduating at the same rate as many college students.

College life

Ted, who has served about a decade, isn’t one to complain about present circumstances. It would be easy though, especially since some of these men have been waiting years for a parole hearing, let alone a release date, and there are bad things happening inside any prison.

“I made the choice that landed me here,” he admitted. “And this is my punishment, but I have the opportunity to do some good for myself and my family.”

Attending class and keeping up with homework gave the class something to look forward to every day, a way to break up the monotonous routine of their lives. Ted said the new regime essentially “saved me” because focusing on the positive helped him avoid the negative of prison life.

Peter, perhaps the oldest in the class with the most time in prison, attributed much of his success in class to his classmates’ moral support, and to Martin, specifically, who became the resident math tutor.

Their favorite course? Microeconomics. Peter said it was the toughest, but most rewarding. The challenge equipped them to approach other subjects, no matter the topic.

Peter said he would encourage others to enroll in Second Chance Pell, claiming “nothing else is more beneficial than a college degree.”

Martin said the college experience inspired him to pay it forward.

“I want to invest in people the way you invested in me,” he proclaimed to Stevens.

“And you will,” she said.

Peter is most grateful for Stevens. Not one for self-promotion, Stevens spun the attention right back.

“Thank you, but I got what I need. It’s right here,” she proclaims, pointing back at each and every one of her students.

Kenny said college has been his opportunity for growth and development, even “a path to redemption.”

Similarly, John saw the experience as a way to be more for his wife and teenage daughters. Their conversations lately have been about the business the family plans to start whenever he is paroled.

For Ted, one of the highlights of college so far was getting to call home and tell his family he talked to Auburn President Christopher B. Roberts. He visited the class earlier this semester.

“It’s easy to lose hope in here, to feel like you only exist,” he said. “But having a day like that, when you get to talk to the university president, it makes you feel like living again.”

Roberts said it was an honor to meet the men enrolled in the program. During the visit, he spoke briefly and then turned it over to the class. He asked them, “What do you want a university president to know?”

“They said this program brought them hope and gave them a purpose while broadening and deepening their perspectives,” Roberts said. “One of the men said he plans to use his degree and the knowledge he obtained to help other people who are incarcerated. It was one of the most fulfilling days of my presidency so far.”

Not one of the students is proud that their past actions resulted in incarceration, but, as Ted said, they are now changed and on track to follow a path to a better life.

“This degree is elevating our possibility for success,” he proclaimed.

“We believe in the power of education,” added Stevens. “Education opens up pathways to be a poet, an accountant, a business owner or an activist.”

Next steps

Many of these students are taking their degrees with the hopes of improving existing family businesses or starting new ones of their own. All will earn a Bachelor of Science in interdisciplinary studies from Auburn, with an emphasis in business, leadership and human development and family science.

Scott noted that the role of universities is to provide students with the knowledge and skills to use in their own lives, perhaps with the hope that graduates will do good in the world, finding solutions to the world’s problems.

“Auburn University is not shirking from that responsibility,” he said, even if it means teaching courses in a state prison.

Martin considers his degree an “awesome product” that has enhanced his life. Until he gets a parole hearing, though, it’s hard not to question his purpose.

“I don’t know where I’m supposed to go from here,” he said.

“You are going to get where you want to,” said Stevens. “This is about so much more than prison. This is about the world we live in.”

A college degree can open up opportunities for these men to do good for themselves, their families and their communities, but there are still some in society who only see them as criminals and keep them from moving beyond their past.

“I would like to use my degree to help others,” said Peter. “I’m in a better position now to do just that.”

Education for all

This college program is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, individual donors and Federal Pell Grants, which are awarded to any person who qualifies economically.

To support this educational opportunity