content body

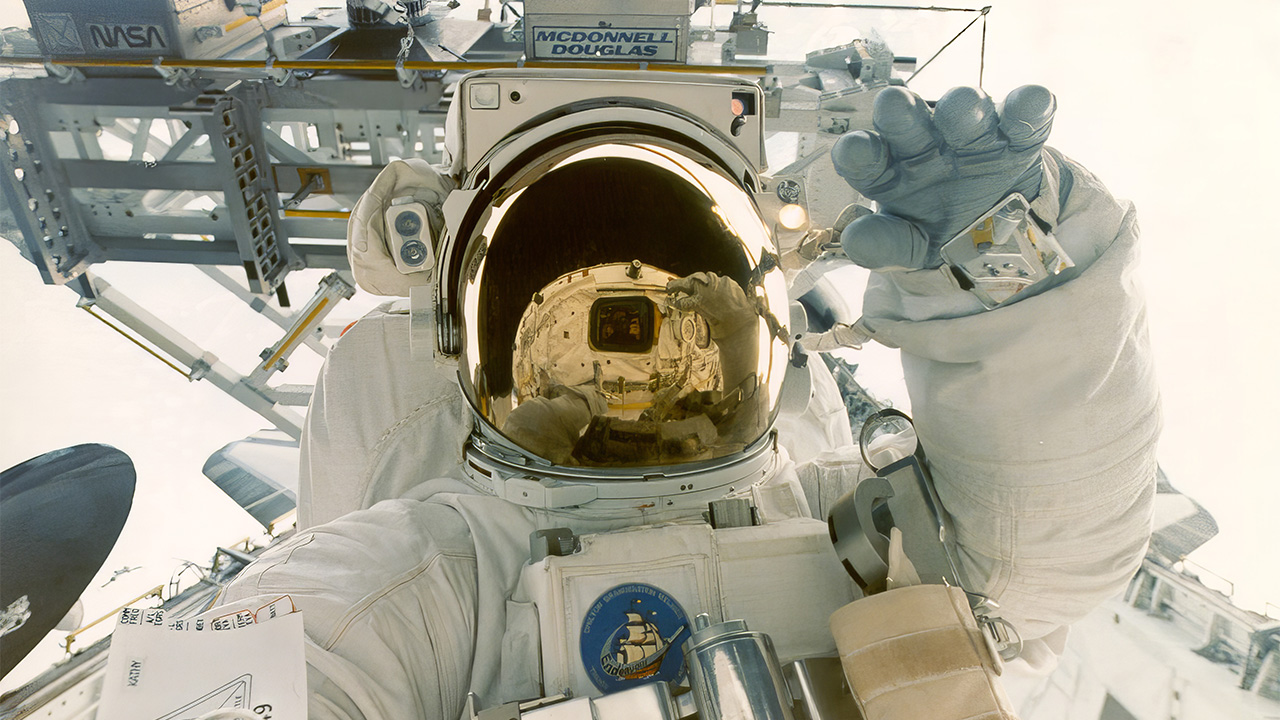

Sometimes former astronaut Kathryn Thornton still daydreams she is back in space. She recalls peering out the Space Shuttle’s window, captivated by the night sky.

“Whether you’re looking at the Earth or the night sky, it’s just fabulous,” Thornton said. “If you find a spot where you think there’s not a star, just hang there for five seconds. You’ll see one.”

It’s not surprising that space has a special place in Thornton’s psyche.

The Montgomery, Alabama, native spent 12 years at NASA and logged more than 975 hours in space over the course of four missions. Among Thornton’s many achievements, she has been inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame, received a doctorate in physics and is now a professor emeritus in University of Virginia’s College of Engineering.

Thornton’s trailblazing career led her around the country and approximately 358 miles vertically, but her academic journey began on the Plains at Auburn where she received her bachelor’s degree in physics in 1974 from Auburn’s College of Sciences and Mathematics.

Photo courtesy of Special Collections & Archives at Auburn University Libraries

Finding a path in physics at Auburn

Growing up, Thornton wasn’t set on a career path — becoming an astronaut wasn’t even on her radar — but she did know one thing: she loved math and science. Thornton’s affinity for science was fostered by her high school science teacher.

“I was generally the only girl in physics classes, and he had the same expectations for me as he did for the guys,” she said. “That was pretty novel at the time.”

Thornton would become accustomed to being one of the only women in the room.

After enrolling in Auburn for her undergraduate studies — a decision Thornton describes as an obvious one — she sequentially tried out different science and math courses to find her right fit.

Math was too abstract. Chemistry laboratories had too much breakable glassware.

But physics was just right.

“In physics, you get to crash cars together and stuff like that,” Thornton said with a laugh. “Who could not like that?”

Thornton excelled within Auburn’s Department of Physics and professors took note, encouraging her to continue studying physics after graduating.

“The professors were very supportive of graduate school,” Thornton said. “I would have never have even thought about it if I had just been left to my own devices or if I were in a larger discipline where I had less individual attention.”

Heeding the advice of her Auburn professors, Thornton enrolled in graduate school in physics at the University of Virginia. While pursuing graduate studies is a significant undertaking, Thornton said, in a certain sense, it was the “path of least resistance” and the next natural step for her.

After receiving her doctorate in 1979, Thornton began a prestigious postdoctoral position at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg, West Germany. Then, in 1980, she began working at the U.S. Army Foreign Science and Technology Center as a physicist.

One day, Thornton noticed an advertisement from NASA — that they were looking for healthy, normal people, advanced degrees desired. Thornton thought: why not apply?

“Applying was kind of the opposite of the path of least resistance,” Thornton said. “It’s one of those things where you dream of winning the lottery and until they draw that number, the dream is alive.”

Auburn has had six alumni become astronauts, including (from left) Hank Hartsfield, Kathryn Thornton, Jan Davis and Jim Voss. Photo courtesy of Special Collections & Archives at Auburn University Libraries.

Cultivating focus, trust as an astronaut

When Thornton got the call in 1984 that she had been selected to become an astronaut, she didn’t have much time to celebrate. She had logistics to settle.

Thornton was based with her family in Virginia, and her unexpected — albeit exciting — new job would require uprooting to Houston. Like many working parents, Thornton continued to navigate work-life tensions after she made the trek to Texas, including when she embarked on her first mission in 1989.

“The hardest thing was to say goodbye to your family, and particularly your kids because we couldn’t see them at least a week before the launch,” Thornton said.

Space exploration suited Thornton. She would go on to become a crew member in three additional missions, including on STS-49 in 1992, where she helped repair the International Telecommunications Satellite, and a year later on STS-61, where Thornton and her crew members restored the Hubble Space Telescope.

Thornton said people may be surprised to discover that only a sliver of an astronaut’s time is devoted to flying in space. Out of her 12 years with NASA, Thornton was in space for 41 days. Technical assignments on the ground can include being in mission control, representing the crew in tests and assisting with other people’s flights.

“I had all kinds of different jobs and experiences while I was not flying that I thought were fabulous,” Thornton said. “I loved supporting other people’s missions.”

Camaraderie and trust between colleagues was a common thread throughout her time at NASA.

“My job was to do my job as best as possible. A lot of people have invested their lives and their careers on the tasks we’re trying to do, so the pressure for me was just don’t mess up,” Thornton said. “At some point, you decide to do it, and then you just don’t sweat the stuff you can’t fix.”

Thornton’s focus and fearlessness helped propel her into places where women were uncommon — from the classroom to the cockpit. These days, Thornton brings some of her grit to hiking the Shenandoah National Park that’s not far from her Virginia home.

“Hiking is type-two fun,” she said. “I feel better when I finish. Especially going uphill, I’ll think, ‘Why am I doing this?’ But I get to the top, and I accomplished this through a series of small steps, even if it’s just one mountain at a time.”

As International Day of Women and Girls in Science approaches on Feb. 11, Thornton said there is significant value in building a team that includes a variety of voices.

“I think we need people of different perspectives — not just gender — but all kinds of different diversity because we all bring our own experiences to the problem,” Thornton said. “If you have more perspectives on a problem, it may take longer to arrive at a solution, but you often arrive at a better solution.”

Learn more about Auburn’s alumni astronauts.

Click here