content body

According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Alabama has suffered more than 87 natural disasters over the past 70 years, including tornados, hurricanes and flash floods.

Several faculty members in Auburn’s Agriscience Education program have teamed with the Alabama Cooperative Extension System (ACES) to ensure the state’s most vulnerable populations are ready for severe weather events.

Many rural counties in Alabama have significant numbers of residents who can’t receive severe weather alerts, often due to language barriers or a lack of consistent Internet access. These populations can include the elderly, the homebound, agricultural workers and families with limited resources. When severe weather is imminent, many depend on word of mouth to warn friends and family.

Jason McKibben, Christopher Clemons and James Lindner, all agriscience education faculty in Auburn’s College of Education, are working alongside Callie Nelson and Amelia Mitchell of ACES to spread the word about the importance of disaster preparedness. Before they began, their colleague Matt Ulmer, a former community development state specialist at ACES, conducted research on disaster preparedness across the state. His findings set the team on a mission to develop two separate programs, funded in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, that are helping rural counties prepare for the worst.

HEADS-UP: community training

To reach those residents who live in rural areas or have limited English, the team created a program titled “HEADS-UP,” which stands for “Helping Every Alabamian Develop Storm Understanding and Preparedness.” As part of this program, ACES’ staff present community seminars called “Be Weather Wise” that help audience members prepare for common natural disasters.

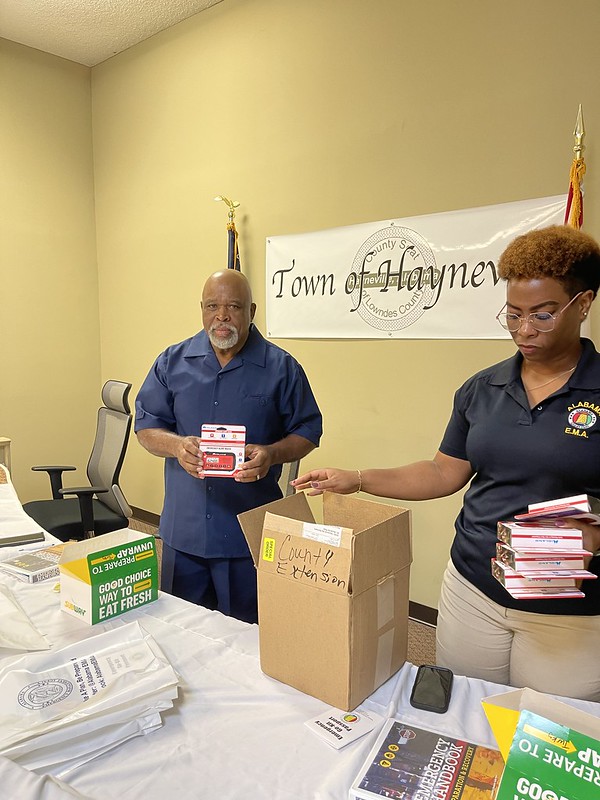

Jimmie Davis, mayor of Hayneville, Alabama, knows that disaster preparedness is serious business as he assists Alabama Emergency Management Agency staff in distributing NOAA weather radios.

These ongoing training sessions cover the difference between watches and warnings and how to identify safe shelter, make a home emergency kit and recover financially from a disaster. Every individual who completes the course receives a NOAA weather radio, along with instruction on how to use it.

County Extension Coordinator Jovita Lewis has presented “Be Weather Wise” sessions at various locations in Hale County, including a church, a community center and the county Extension office. She was surprised by the popularity of the events and happy to see the response was overwhelmingly positive.

“Just one social media post, shared 15 times, prompted calls to the Hale County Extension office from individuals who did not have a weather radio in their home,” said Lewis. “Reservations for the first workshop filled up fast, leading to the offering of more workshops in September and October. With the onset of recent tornados and inclement weather in Hale County, participants said they felt better prepared for weather disasters.”

County Extension Coordinator Tana Shealey, who works in Lowndes County, distributed 40 weather radios this past fall and will distribute another 20 this spring. Shealey, whose efforts focused on the small, rural communities of Mount Willing, Hayneville and White Hall, thinks the educational materials are extremely helpful.

“ACES has compiled a really handy booklet on things you can do to plan, mitigate and recover from severe weather,” Shealey said. “For example, there is a section in the Extension Emergency Handbook that helps us determine what food is safe to eat after a storm causes a power outage.”

In addition to community training, the HEADS-UP program also introduced a state-wide communications campaign in print, broadcast and social media to educate the public on severe weather preparations, storm classifications and financial preparedness for disasters. This campaign specifically targets populations that are most often impacted by severe weather, including agricultural workers and those living in substandard housing.

“A natural disaster often has the greatest impact on the people who are least prepared to deal with it, which is those who lack connectivity and community support systems,” said McKibben.

He and the team are grateful for partnerships with organizations who do the heavy lifting on this project, especially the Alabama NAACP and the Alabama Coalition for Immigrant Justice (ACIJ). These two organizations have helped to organize, translate and conduct trainings.

“The NAACP and ACIJ have helped us bring information to the communities that need it most,” he said. “Residents of rural areas may trust these organizations more than they would us, so we are grateful for their partnerships. We don’t need the credit. We’re just happy the work is being done.”

Want to make sure you're prepared for a natural disaster?

Review ACES’ Emergency Handbook online.PEER-SLN: Coordinating disaster response

The second program is titled “Preparing Emergency Education Responders through Sustainable Learning Network Modules” (PEERSLN). While the name of the program is long, it describes exactly what the team has accomplished — the creation of learning modules and presentations for emergency management officials.

“We’re trying to get folks together to help create community action plans for when disasters happen,” McKibben said. “Most cities have those, and some counties do too, but when you get into some of our less connected areas, there may be no plans in place at all.”

The program is intended to train state and county-level teams to coordinate their disaster responses with Extension professionals, government officials and local volunteer organizations.

McKibben, Ulmer and their former ACES colleague Emery Tschetter began PEER-SLN after their research revealed an alarming lack of understanding of storm preparation practices among emergency managers. They used that data to decide where they most needed to focus their efforts.

An Extension volunteer in Hale County, Alabama, helps a resident program her NOAA weather radio.

“We looked specifically at what disasters communities might think are most likely and are least prepared for,” McKibben said. “A hurricane in Muscle Shoals is not exactly a problem, but there are often wildfires in the Black Belt, so knowing where to start was important.”

Now, Extension personnel from 18 counties are helping to organize groups that work together to create disaster preparedness plans for their communities. They use a curriculum called “Ready Community,” originally designed by the Southern Rural Development Center at Mississippi State University, as the starting point. McKibben and his colleagues edited and localized those materials for Alabama and prepared presentation materials for Extension agents.

County Extension Coordinator Katie Shepard of Baldwin County has been working with the rural communities of Perdido Beach, Lillian, Elberta and Josephine to ensure they are prepared for hurricanes and other natural disasters.

“The Baldwin County Emergency Management Agency has a great emergency operations plan, but the goal is for these smaller communities to have their own plans,” Shepard said. “If flooding happens in Perdido Beach, we’ll know who is in charge and who will organize volunteers.”

Because rural communities might not have emergency management officials to take charge, Extension is helping to identify and train individuals who can lead an emergency plan.

“These emergency management coordinators wear other hats, so they may not have any background or experience in this,” Shepard said. “It may be the fire chief, or in one of these towns it’s the manager of the homeowner’s association. The idea is that we get them organized and prepared.”

McKibben believes building connections between rural communities and larger emergency management agencies is extremely important work that can save lives.

“A city like Auburn will have a plan, but if you go into the smaller outlying communities, they may not,” he said. “So, we need to help the community leaders there. Are they the local businesspeople? The ranchers and farmers? We can all work together to build a community plan.”