content body

Every time Nina Stute’s family asks her to transfer to medical school, she struggles to explain why she just can’t just leave her research in the field of neurovascular physiology.

“Everyone has an underlying reason for getting into this, and mine has always been wanting to decrease human suffering,” Stute said. “That’s been my M.O. since I was little, and I feel I can do that better and have a larger reach through research.”

‘Cooler than studying for the LSAT’

Stute is a prolific researcher, and she’s not even halfway through Auburn’s Doctorate in Kinesiology program in the College of Education. A Presidential Graduate Research Fellow, she already has more than 20 publications to her name, and she’s currently conducting research on health disparities in her work as a Rural Health Fellow.

Given all her accomplishments, it’s hard to believe Stute wasn’t always interested in scientific research.

“I was a business major at Ohio State, thinking of pursuing law school, when I volunteered as a research assistant in a sports performance lab,” she said. “I thought to myself, ‘Wow, this is so much cooler than studying for the LSAT.’ So, I took an extra year of science — physics, chemistry, everything I needed to get into grad school — and earned a scholarship to Appalachian State University in North Carolina.”

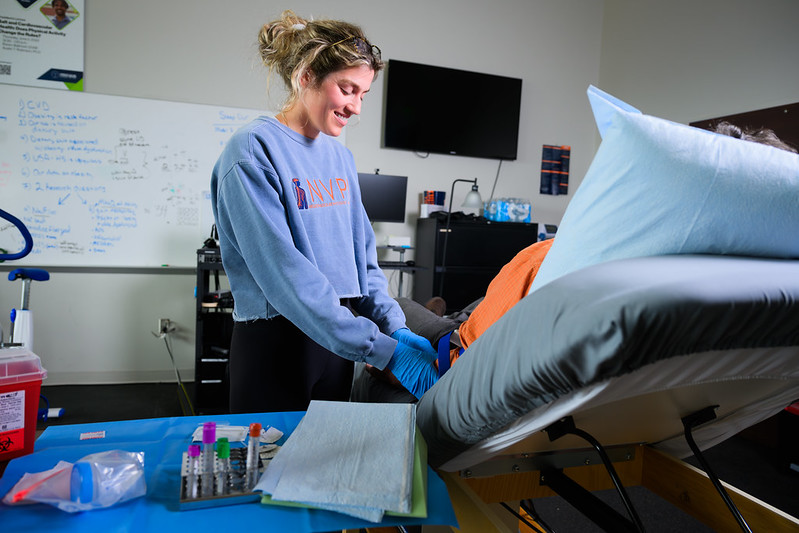

It was there Stute became trained in microneurography, a technique where a needle electrode is inserted in a person’s peripheral nerve — while they are awake — to measure electrical activity and evaluate aspects of cardiovascular health. There are only a handful of scientists who can practice microneurography in the United States, and it’s the main reason Stute was recruited to study and work in Auburn’s Neurovascular Physiology Lab.

Although the lab is equipped for microneurography, Stute most likely won’t utilize it as she completes her dissertation over the next two-and-a-half years.

“Microneurography is not super painful, it’s just uncomfortable,” she said. “It’s also time-consuming and expensive. I want to look at things we can do that are faster and less invasive, give us good data and leave participants with a good experience.”

Research in a rural setting

The desire to leave participants with a good experience is where Stute’s work as a Rural Health Fellow comes in. She is planning to conduct her dissertation research both on campus and at the Chambers County Community Health & Wellness Center in LaFayette, Alabama.

The Rural Health Fellows program, an offshoot of Auburn’s Rural Health Initiative, aims to train future health care leaders to create positive change in health equity. After a rigorous application process this past fall, the seven students who were named fellows are now gaining experience in rural health care by attending monthly meetings, completing online course modules and designing and implementing health-centered activities in the LaFayette community.

For her activity, Stute is offering participants a 90-minute health assessment that includes comprehensive health history questionnaires, measures of blood pressure and arterial stiffness and an ultrasound to quantify blood flow through the kidney. In the molecular lab, Stute will also collect urine and blood samples to run experiments that quantify biomarkers of inflammation, cardiovascular health and kidney function.

While data from the assessments will answer her research question of whether hydration practices can decrease cardiovascular risk, Stute also hopes the information is helpful to her participants.

“We have to remember we’re not medical doctors, and we can’t practice medicine, but we can do a lot of tests for free that could cost thousands in a doctor’s office,” Stute said. “A big thing for me is health literacy and explaining things in a way participants can understand.”

Can hydration decrease the risk of heart problems?

Once these assessments are completed, Stute will ask participants to increase their fluid intake for two weeks, with some participants also supplementing with potassium and others serving as a control group. After the two weeks, she will repeat assessments to determine if increased water intake and potassium supplements affect cardiovascular health and kidney function.

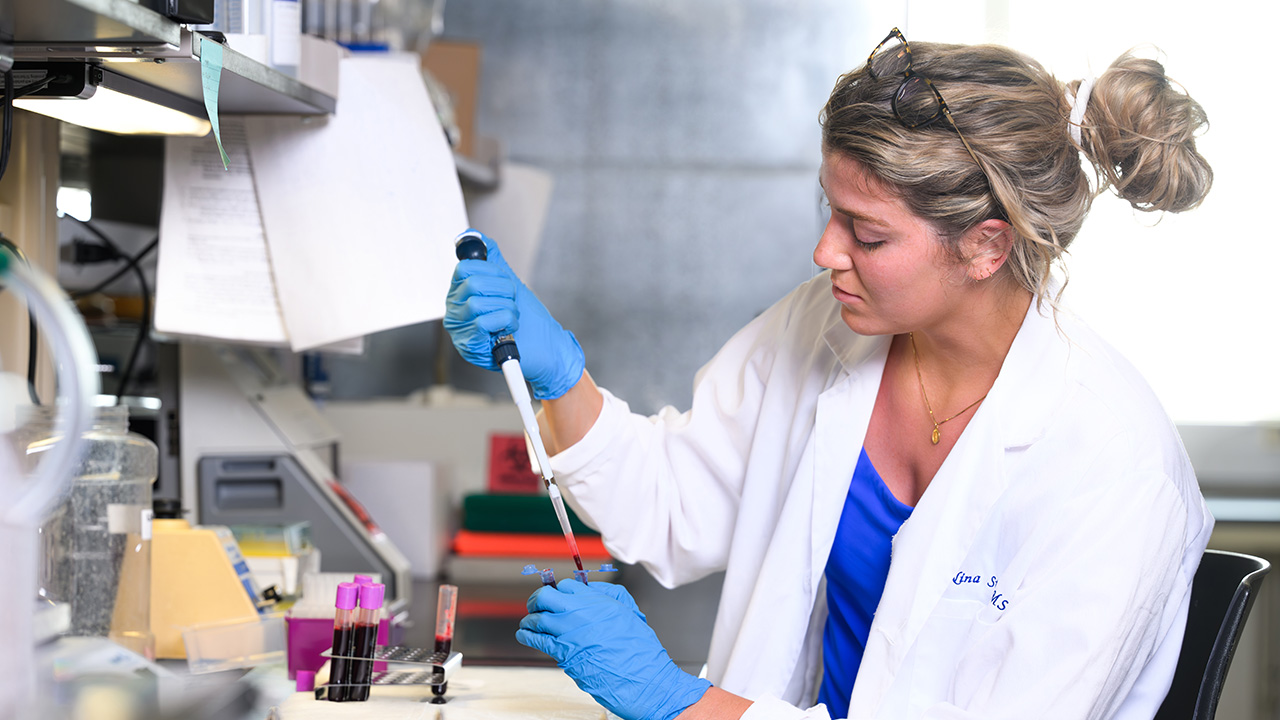

“All my master’s research with microneurography focused on the applied human aspect, but now I’m focused on the basic molecular aspect,” she said. “It’s great because it’s forcing me to develop these molecular wet lab skills I didn’t have. I’m most excited for the blood and the urine — I know that probably doesn’t get most people excited — but to do assays on that is going to be really interesting and will hopefully help us tease out some novel findings.”

Researching both inside and outside the lab

When Stute says she’ll be doing assays, she’s referring to experiments that quantify certain biomarkers in the blood and urine samples that can help her and her team understand what is happening at the molecular level. Some of the molecular lab equipment she’s using includes an osmometer and refractometer to study hydration levels, an electrolyte analyzer to determine sodium, potassium and chloride levels, a Spectramax iD3 plate reader to assess protein content and a Cholestech analyzer to get complete lipid profiles and measure cholesterol and blood glucose.

Beyond her dissertation research, Stute hopes to utilize the mentorship and connections the Rural Health Initiative offers to apply for more grant funding. The molecular skills she’s honed at Auburn open many doors for potential funding opportunities, as well as for developing novel ways to battle different diseases.

While Auburn faculty, staff and students are accustomed to hearing about ongoing research studies, it’s less likely residents of rural Alabama can say the same. Stute is excited to be out in the community, sharing her wealth of knowledge in neurovascular health with those who participate in her study.