content body

Auburn Assistant Professor Aniruddha Belsare has developed an application called ZeroRabiesApp that provides critical information and tracks the availability of life-saving medications.

As a veterinarian in rural India, Aniruddha Belsare witnessed firsthand the plight of rabies. He watched in horror as teenagers bit by rabid dogs failed to receive the necessary lifesaving treatment.

Over the years, Belsare, now an assistant professor of disease ecology within Auburn’s College of Forestry, Wildlife and Environment (CFWE), shifted his focus from practicing veterinary medicine to studying infectious diseases of animals. His project topics include chronic wasting disease in North American deer populations and others that have implications for public health and conservation.

But along the way, he fixated on the needless rabies deaths he struggled to prevent in India, and one day he determined to take matters into his own hands.

“I realized this will keep on happening unless and until getting these medications becomes easier,” Belsare said.

In 2021, Belsare began developing an application called ZeroRabiesApp that provides critical information about dog-bite treatment and also tracks the availability of lifesaving medications in developing countries, such as India and Nigeria. In a recent preprint publication, Belsare and his international collaborators outline their strategy for preventing human rabies deaths through their interactive web application.

The wrath of rabies

Rabies is one of the deadliest and yet most preventable diseases in the world. After being bit by an animal carrying the rabies virus, people are nearly guaranteed to die within a few days. But those who receive the proper post-exposure treatment promptly always recover to full health.

In the U.S. and much of the Western world, responsible pet ownership, pet dog vaccination and access to post-exposure treatment have made rabies deaths nearly obsolete.

But the story is very different in many African and Asian countries, where large stray dog populations are largely unvaccinated and rabies treatments are much less accessible. In India, someone dies from dog-mediated rabies roughly every 30 minutes.

“These are 100% preventable deaths,” Belsare said. “Something has to be done to save lives today.”

There are two main problems that perpetuate the rabies cycle in places like India, Belsare said. First, people in remote, rural areas are often misinformed about how essential it is to receive post-bite treatment after a potential rabies exposure. Some wrongfully assume they can wait until symptoms appear to seek medical care. Others avoid treatment because they fear they will have to receive a dozen painful shots in the abdomen, which was the case a few decades ago.

But these days, the typical treatment plan — called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) — consists of four intramuscular injections of rabies vaccine delivered over the course of two weeks and a dose of rabies antiserum bite wound.

The second issue is one of accessibility. The PEP biologics are sparsely distributed throughout rural areas, and finding the right medications often involves “a lot of running from pillar to post,” Belsare said. When prompt treatment is so urgent, knowing where biologics are in stock nearby is often the difference between life and death.

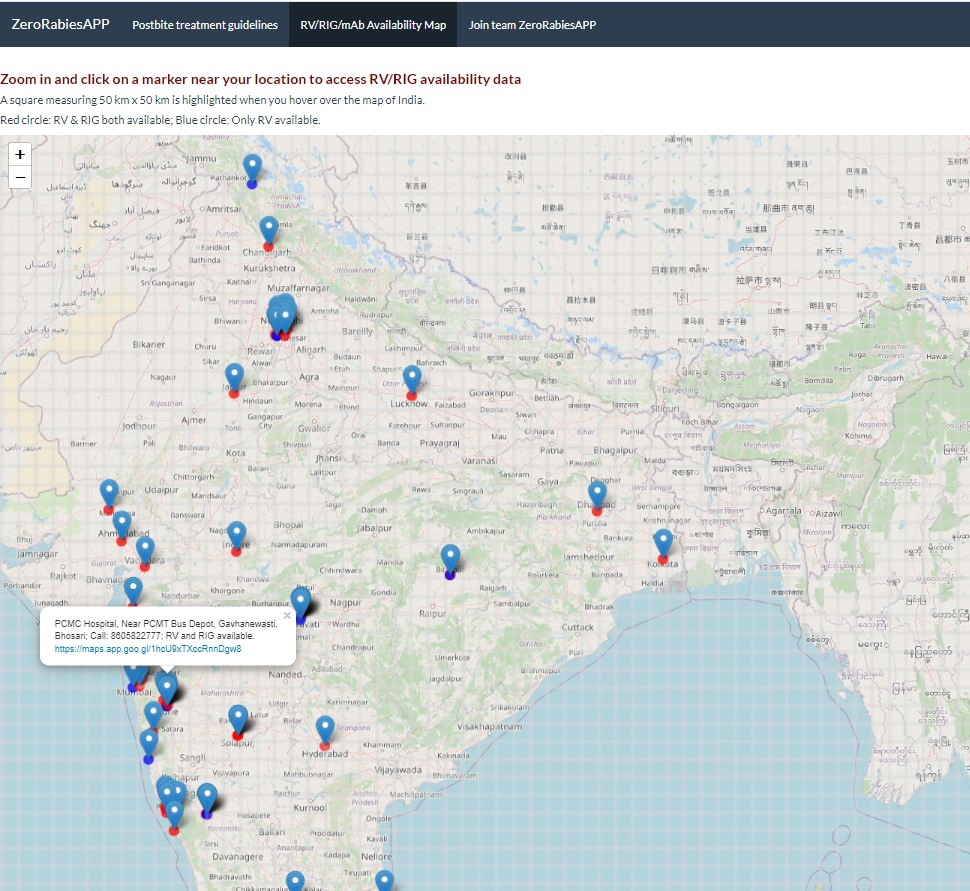

The RV/RIG/mAb Availability Map in the ZeroRabiesAPP (ZRA) is connected with a rabies biologics database. Red circles indicate availability of rabies vaccine (RV), rabies immune globulin (RIG), and/or rabies human monoclonal antibodies (mAb) while blue circles indicate availability of rabies vaccine only.

Auburn joins the fight

As a cross-disciplinary researcher at Auburn, Belsare is working to fill both of these gaps. His ZeroRabiesApp sources current post-bite treatment guidelines directly from the World Health Organization and Center for Disease Control to offer a clear, customized treatment plan based on the time of exposure.

With the help of nonprofits and citizen scientists, the app features a database of rabies biologics available in pharmacies and health care facilities across the country. The crowdsourced approach relies on volunteers to contribute the rabies biologics availability information through an online portal.

“The hope is to build upon this app to inform efficient rabies control strategies,” Belsare said, and he aims to bring in undergraduate and graduate students to help him with this larger initiative.

The application is currently in use in India and Nigeria, and Belsare hopes to expand it to other countries with high rabies death rates. To do so, he’s working to recruit help from students and funding agencies. He aims to have at least 1,000 rabies biologics availability locations for India, and he also plans to build a version of the app that works without internet connection.

The CFWE provides Belsare with support to pursue the ZeroRabiesApp as a passion project. His rabies project dovetails with his other disease modeling work at Auburn to address his broader goal of conquering overlooked diseases that impact human and wildlife health.

“Diseases like rabies are neglected for a reason,” Belsare said.

Because they primarily impact poor communities and are often underreported, they tend to fall low on the priority list for government agencies. Belsare hopes that independent initiatives like his can support these overlooked cases and help meet the target of eliminating all deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030, as laid out by a coalition of international organizations in 2015.

“These are very simple, straightforward things that need to be done,” Belsare said. “People should not continue to die from a disease we have all the tools to conquer.”