content body

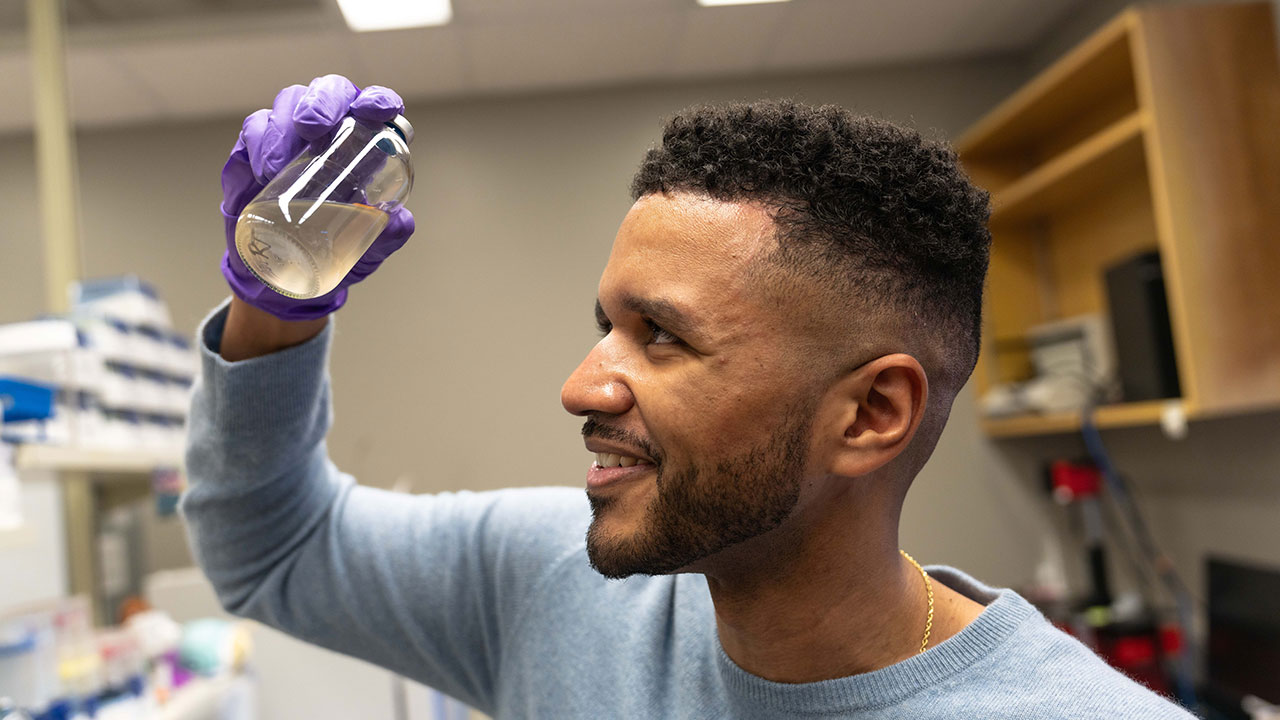

Rodney Tollerson II is on a quest for answers.

Like most researchers, the microbiologist longs to find explanations for the unexplainable, to discover new insights in the realm of science and learn more about the complex world that surrounds us. By doing so, he hopes to make an impact on the planet that will benefit all and to fulfill his chosen path as a scientist and educator.

The 31-year-old Savannah, Georgia, native is hard at work in the lab and the classroom in his role as an assistant professor in the College of Sciences and Mathematics’ Department of Biological Sciences. Tollerson’s research primarily focuses on microbial methane metabolism processes and the ways microbes might adapt and respond to varying or changing environmental factors. The work, he said, is designed to find answers to a litany of questions, including how methane production might be decreased in the environment beginning at the microbial level.

“One of the major goals of the lab is to understand the way that methane production is regulated by the organisms,” said Tollerson, who earned his doctorate at The Ohio State University. “We are looking at this at the genetic level to see what genes are being made to lead to the production of methane and how the cell turns that gene on or off depending on its environment.

“So, we use a lot of genetic tools, and we do a lot of molecular biology and sequencing to determine if a gene is being made in a certain amount under a certain environment. That’s a big aim of the lab we are interested in right now.”

His work and role as a professor propel Tollerson’s efforts, and he already has made an impact on campus. He may only have been an Auburn University faculty member for a year, but Tollerson is thoroughly enjoying work and life on the Plains.

“One thing I really like about Auburn is having that community feeling where everyone treats you like a friend because they know you’re having a shared experience,” he said. “At the university, I really feel like I’ve been supported at the college level with the dean, at the departmental level, everywhere.”

Rodney Tollerson and his lab students use things like liquid nitrogen to agitate molecules and study how environmental factors affect methane production.

Interesting path to science, Auburn

Tollerson, who moved frequently as a child and attended high school in Chicago, gravitated to the world of microbiology by accident.

“When I started college, I actually started in microbiology by, I guess, serendipity,” said Tollerson, who earned his undergraduate degree in microbiology from the University of Arizona. “I did not know what microbiology was. I was interested in insects, and so I thought by microbiology they meant bugs and things like that.

“I got into microbiology and realized, ‘Oh, that’s not what I thought it was.’ But what I was learning, I was like, ‘This is actually cool.’”

Once Tollerson was bitten by the microbiology bug, so to speak, the next “light-bulb moment” involved his unrealized love of research. After working in an undergraduate research lab that studied food microbiology, he was exposed to genetics and molecular biology during a research experience at the University of Iowa.

“That was my first foray into genetics and molecular biology, which is what I do now, and I was actually completely horrified of it because I had never done anything like that before,” said Tollerson, whose doctoral dissertation focused on the E. coli bacteria. “I went into it like, ‘Well, it’s a completely foreign world, but I’m going to try to immerse myself in it for a couple of months. If I hate it, well, at least I learned something.’

“But then it turned out that I loved it, and so that’s why I was like, ‘I think I want to do molecular biology, microbiology, for my Ph.D. and career.’”

With family roots still strong in the South, Tollerson applied for a full-time faculty position at Auburn after completing his post-doctoral work at the California Institute of Technology.

“I wanted to get back near family, and Auburn really provided the best position for me to grow and be the type of faculty I wanted to be,” Tollerson said. “So, it was the perfect opportunity and seemed like the perfect match.”

He has settled in nicely in the town and the university and is off and running as a researcher and educator.

Mentoring students is one of the most fulfilling aspects of Rodney Tollerson's role as assistant professor at Auburn University.

Dedication to inspiring students

As an educator, Tollerson hopes to inspire students to develop a curiosity for science and explore the topics that intrigue them most.

“I try to introduce students to molecular biology in the way that research works at the undergrad stage and in a classroom setting,” he said. “If you show them the science that’s going on, that can for some students be like, ‘Oh, this is stuff we don’t know.’ I love when they start asking questions and we get to the point where I say we actually don’t know.

“And then I always tell them right after that, if they’re interested, they should do research.”

Tollerson admits his approach to teaching may be a bit unconventional at times, aligning more with introspective thought than rote memorization of scientific information.

“I’ll say, ‘OK, we’re going to look at one slide for 20 minutes, and I’m going to let you ask questions about it and let you come up with your own ideas,’” Tollerson said. “At first, students are timid, but then over time, they’re coming up with their own thoughts. I had a class last semester where I only got through one slide for the whole hour and 15 minutes of class.

“That’s the stuff I love, because it means that we’re diving deep into the material. We’re starting to think about it, and that’s fulfilling for me. You can drill deep, and that has a deeper meaning for them when they leave.”

Tollerson also has lofty goals for the students and staff who put in time in his lab.

“When you’re in my lab, I want people to come up with their own questions,” he said. “If I can think of everything myself, there’s no point having anybody else in the lab. One of the things I strongly believe in is my students and everyone who’s training under me has ownership of their project.

“I really want people to have their own intellectual curiosity and be able to explore that in my lab. That was something I was able to do in my education, and I think that led me to fall in love with research.”

Grace Britt, a recent microbiology graduate, enjoys working as a technician in Tollerson’s lab.

“It’s been great,” she said. “He’s the smartest person I’ve ever met. He’s inspiring and pushes us to do things on our own but is also there to help us. We have a lot of fun in the lab, which is a nice aspect of the work.

“I just think it’s cool to be able to come to work every day and learn.”

Recent graduate Grace Britt has enjoyed working with Tollerson in the lab for nearly a year.

A hunger for understanding

Once Tollerson determined his research niche would involve an intersection of microbiology and genetics, he zeroed in on a problem to solve — how methane excess negatively affects the environment.

“My interests are in microbes that help control the way our climate works,” he said. “I study this domain of life called Archaea, which is quite interesting because they’re microbes like bacteria. So extremely small microbes, but they’re more closely related to humans than they are to bacteria, which is an interesting thing.”

One particular yin-yang scenario involving microbial organisms is particularly fascinating to Tollerson and his research team.

“A lot of these organisms are what we call methanogens, and they are called that because they make methane,” he said. “I’m interested in the way those microbes respond to different perturbations, like changes in temperature or a change in acidity since our oceans are becoming more acidic. Are they going to make more or less methane?

“We also are interested in how methanotrophs — which eat methane — are going to respond, because if they consume less, that means more is getting out into our atmosphere. That fascinates me because I think it’s something that can produce a tangible change through our research.”

By learning more about methane production, Tollerson hopes to one day be able to formulate methods to reduce it in the environment, which could slow global temperature increases and other troubling trends that are ripple effects of a central problem.

“I think the thing that would be most important is the predictive power of what we can do in the laboratory,” he said. “The goal is to try to slow atmospheric temperature increases, or at least understand them. If we can understand just one small portion of this, which is the methanogen or the methanotroph, then we can potentially model things better.

“We can predict better what’s going to happen in the future and maybe start engineering the methanotrophs in a way that we can grow them in the lab in big enough amounts that they can start pulling methane out of the atmosphere, enough to have a tangible impact on our planet.”

Tollerson and his colleagues believe a meaningful breakthrough in methane reduction is a real possibility.

“It’s something tangible we can see,” Tollerson said. “This is something we’re doing, and this is how we’re trying to make our mark on the world.

“It’s right there, and I think there’s no better place to do it than here.”

"He’s the smartest person I’ve ever met. He’s inspiring and pushes us to do things on our own but is also there to help us. We have a lot of fun in the lab, which is a nice aspect of the work."